This site is the archived OWASP Foundation Wiki and is no longer accepting Account Requests.

To view the new OWASP Foundation website, please visit https://owasp.org

Difference between revisions of "Credential stuffing"

Neal Mueller (talk | contribs) (→Related Attacks) |

Neal Mueller (talk | contribs) (→Related Threat Agents) |

||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

== Related Threat Agents == | == Related Threat Agents == | ||

| + | * [[:Category:Authentication]] | ||

== Related Attacks == | == Related Attacks == | ||

Revision as of 21:14, 3 February 2015

- This is an Attack. To view all attacks, please see the Attack Category page.

Description

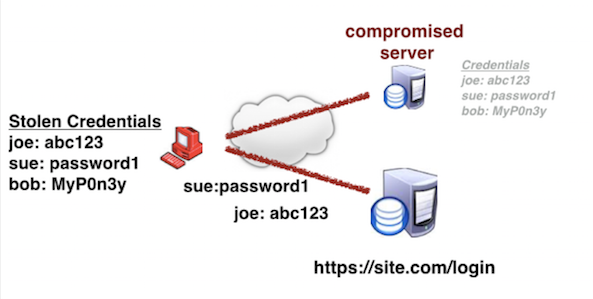

Credential stuffing is the automated injection of breached username/password pairs in order to fraudulently gain access to user accounts. This is a kind of brute force attack: large numbers of spilled credentials are automatically entered into websites until they are potentially matched to an existing account, which the attacker can then hijack for their own purposes.

Severity

Credential stuffing is one of the most common techniques used to take-over user accounts.

Anatomy of Attack

- The attacker acquires spilled usernames and passwords from a website breach or password dump site.

- The attacker uses an account checker to test the stolen credentials against many websites (for instance, social media sites or online marketplaces).

- Successful logins (usually 0.1-0.2% of the total login attempts) allow the attacker to take over the account matching the stolen credentials.

- The attacker drains stolen accounts of stored value, credit card numbers, and other personally identifiable information

- The attacker may also use account information going forward for other nefarious purposes (for example, to send spam or create further transactions)

The above diagram was made by Michael Coates [1]

Risk Factors

TBD

Examples

Below are excerpts taken from publications analyzing large-scale breaches. Evidence supports that these breaches were the result of credential stuffing.

- Sony, 2012: “I wish to highlight that two-thirds of users whose data were in both the Sony data set and the Gawker breach earlier this year used the same password for each system.”

- Yahoo, 2013: “What do Sony and Yahoo! have in common? Passwords!”.

- Source: Troy Hunt. [4]

- Dropbox, 2013: “The usernames and passwords referenced in these articles were stolen from unrelated services, not Dropbox. Attackers then used these stolen credentials to try to log in to sites across the internet, including Dropbox”.

- Source: Dropbox. [5]

- JPMC, 2014: “[The breached data] contained some of the combinations of passwords and email addresses used by race participants who had registered on the Corporate Challenge website, an online platform for a series of annual charitable races that JPMorgan sponsors in major cities and that is run by an outside vendor. The races are open to bank employees and employees of other corporations”.

- Source: NY Times. [6]

This connected chain of events from Sony to Yahoo to Dropbox excludes JPMC. The JPMC breach came from a separate and unrelated source. We know that the JPMC breach was caused by attackers targeting an unrelated third-party athletic race/run site for credentials to use against JPMC.