This site is the archived OWASP Foundation Wiki and is no longer accepting Account Requests.

To view the new OWASP Foundation website, please visit https://owasp.org

How to Build an HTTP Request Validation Engine for Your J2EE Application

Author: Jeff Williams, Aspect Security

- 1 Overview

- 2 Requirements for an HTTP Request Validation Engine

- 2.1 Rules Are Powerful and Simple to Specify

- 2.2 Handle Extra, Missing, and Malformed Parts

- 2.3 Support Fatal, Continue, and Ignore Actions

- 2.4 Easy to Change and Test Rules

- 2.5 Validate All Parts of the HTTP Request

- 2.6 Apply Rules to Any Part of Web Tree

- 2.7 Enable Same Validation on Client and Server

- 2.8 Support Customized Error Messages

- 2.9 Support Multiple Rules for the Same Part

- 2.10 Easy to Integrate

- 2.11 Secure by Default

- 2.12 Simple and Obvious API

- 2.13 Stinger - A Simple Powerful Validation Engine

- 3 An Alpha Stinger Implementation

Overview

"Never trust anything from the HTTP request." That's rule number one for web application security. If you fail, you open your application to many different forms of injection, overflow, and tampering. So validate everything, before you use it, right? It always sounds so simple, yet most development projects ignore the requirement or implement it very haphazardly. There are many alternative methods of implementing validation, but which is the best? In this article, we'll discuss approaches for validating all of the different parts of the HTTP request. Once we've nailed down a few requirements, we'll use the new regular expression package in Java 1.4 to demonstrate one way of implementing validation. "Rule #1: Never trust anything from the HTTP request!"

When you think of security mechanisms, you usually think of encryption, authentication, access control, and even logging. But people rarely talk about validation as a security mechanism. I find this odd, since validation plays such a key role in protecting web applications against attack. In future articles, I'm going to focus on some of the other bastard children of the security world, like error handling, thread safety, and key management.

I can't stress enough the importance of taking time to actually design a validation scheme for your web application. Simply by putting a unified mechanism in place, you'll send a strong message to the rest of the development team that the HTTP request information must be validated. If you've got an application already, you can find out quickly whether you're properly validating. First, search your code for HttpServletRequest calls to getCookies(), getHeader(), getHeaders(), getIntHeader(), getQueryString(), getParameter(), getParameterMap(), and getParameterValues(). Then check to see if the values returned from these calls are carefully scrubbed before they get used.

As I realized once I started writing them down, an API to validate an HTTP request has more requirements than I thought. There's a brief discussion of each requirement below. At Aspect, we review a lot of code, so I have some very definite ideas about which approaches work and which do not. I've also borrowed a bit from the principles that Elliotte Harold (author of Cafe au Lait) detailed when designing XOM.

Developers should not need to be either security or Java experts in order to use a validation engine. The primary goal of the engine design should be to make the most common activities easy, so the interface must be simple, intuitive, and consistent. Most developers will not have to refer to the documentation to get the API integrated into their web applications. There are really only three steps to using validation, setting up the rules, invoking the checker, and handling any errors that are found. So, let's discuss some overall requirements and the key requirements for these three areas. The last half of this article introduces Stinger, a simple implementation that attempts to meet these requirements.

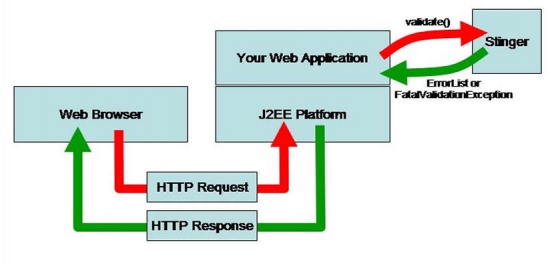

The driving requirement is to assign a regex to every part of each HTTP request. The basic flow is shown in the figure below. The web application hands off to the Stinger validation engine and gets back either a list of errors or an exception. If the list of errors is empty, then no errors were found.

Requirements for an HTTP Request Validation Engine

Rules Are Powerful and Simple to Specify

Each HTTP request is going to need to be validated against a set of rules. There are many options for specifying validation rules. The most common approach is to write code that manually parses and checks input for certain characteristics. This is a poor approach, as it requires a lot of custom coding and is difficult to do consistently. In the XML world, you could use a DTD or schema to define validation rules, but those engines aren't easily applied to web traffic - believe me, I know. A very powerful approach is to use regular expressions to represent the rules for each part of the HTTP request. Regular expressions take a little while to become comfortable with, but are so powerful that for web applications, I believe they represent the best balance between simplicity and power. To save everyone's time, the engine should include the ability to maintain a library of commonly useful regular expressions.

Handle Extra, Missing, and Malformed Parts

The types of problems that the engine must handle fall into three major categories. The first is "extra" headers, cookies, or parameters that have no business in a web request to your application. I've only ever seen one web application that checked for extra parts, but it's a pretty good idea. There's no reason why those parts would be present in ordinary traffic, but attack tools might add these extra parts. So the engine must be able to flag those extra parts. The second problem is "missing" parts that are required to show up in a request. Of course, some parts are optional, so there has to be a way of allowing optional parts to be missing. The third type of problem is "malformed" parts, these are expected parts where the value does not have the correct syntax.

Support Fatal, Continue, and Ignore Actions

There's no right way to respond to a bad HTTP request. The response depends on your application and should be tailored to the precise error that occurs. You might want to continue processing and do the best you can to generate a useful response. Or you might want to sound an alarm and shut down the system. You can resend a form with invalid fields marked in red. Or you might want to track errors across several requests and block a user that sets off too many alarms. It all depends on your application. So the best the validation engine can do is to provide detailed information about what went wrong and let the developer handle them appropriately. The engine should allow a separate action and error message depending on whether a part is extra, missing, or malformed.

The engine should allow marking some rules as "fatal" -- stop processing and throw an exception. This allows the developer to handle the exception in the main servlet or JSP and produce a short error screen. This action should be used for requests that should "never happen" or requests that are likely to represent an attack. For example, if the JSESSIONID cookie shows up with anything but 32 characters from the set [A-F0-9] then something is deeply wrong. By stopping the validation process, you don't waste time processing attack traffic.

Most of the time, however, rules should be marked "continue" -- keep validating all the parts of the HTTP request. In this case, the engine must build a list of errors that the developer can format into a list for the user. This mode allows giving users a list of errors, instead of an annoying one error at a time.

There is one more action the engine should support, the "ignore" action. Frequently, you'll want use the ignore action when part of the HTTP request is missing. This is a way to specify an optional header, cookie, or parameter. Further, the ignore action should be used to delegate responsibility for checking certain parts of a request to other rulesets. So, for example, you might create a ruleset that applies to all requests and set it to ignore missing form field parameters. Then you can set up specific rulesets for each page containing a form.

Easy to Change and Test Rules

Regular expressions aren't the most obvious language in the world, and it typically takes a bit of trial-and-error to get the rules right. One way to help with this problem is to include a wide variety of pre-defined rules for common types of checks. But it also has to allow the rules to be changed without recompiling or restarting the web application, to make testing new validation rules easier. The engine should allow creating rulesets programatically, but there should also be a way to store the rules in an XML format. It would be nice if the engine would detect changes in the files and reload them without requiring a restart of the web application.

Validate All Parts of the HTTP Request

A validation engine should allow developers to specify rules for all the parts of the HTTP request, including URL, querystring, headers, cookies, hidden fields, and other form fields. Attacks aren't limited to form fields, and neither should your validation framework. The framework should use the same approach for validating all parts of the HTTP request, since it just adds complexity to have more than one validation system.

Apply Rules to Any Part of Web Tree

Most validation rules apply only to a single form field, but what about the rules for cookies on a part of the site, or headers across the entire site? Our validation scheme should allow developers to specify the rules that apply to parts of a site or even the entire site. Building on the approach used for J2EE filters, the best approach here seems to be to associate a set of rules with a path. We'll apply the rules to any request that matches the path.

Enable Same Validation on Client and Server

I'm not a huge fan of client-side validation -- using JavaScript to check that the form is filled out properly. Client-side checking is trivial to bypass and absolutely irrelevant to security. It may even do some damage if developers don't know about security and rely on the client-side checking. Still, if you've decided to have client-side checking, you should do exactly the same checks on the client that you do on the server. It would be nice if the validation engine would generate a script that will validate forms with exactly the same tests that will be performed on the server. Some might argue that you shouldn't give away the validation patterns, but I don't think there's much risk there. It's like telling everyone you're using Blowfish to encrypt data doesn't make it easier to crack.

Support Customized Error Messages

Detailed error messages should be available for the developer to use if necessary. There are many cases when these error message should not be sent to users. You would never want to give an attacker a detailed message specifying the session id format. However, in many cases, specific messages will help users fill out forms properly and can be used in detailed log entries to help uncover attacks. The framework should generate default error messages if no custom message is specified. There should be a provision to prevent the use of sensitive information, such as credit card numbers and passwords, from being echoed back in an automatically generated error message.

Support Multiple Rules for the Same Part

The engine should provide a way to put multiple rules on a single part of an HTTP request, each with a custom error message. So, if a password field entry is too short, the error message might say, "Passwords must be 8 characters or longer." But if the same password contains an illegal character, like a semi-colon, the message should say "Passwords must only use alphanumeric characters."

Easy to Integrate

Really, the best design for this engine would be to build it into the J2EE platform. Then validation could be a standard part of accessing URLs, forms, cookies, and other headers. But there's no provision built into J2EE for validating all that information in a standard way. So we have to build an engine that is easy to integrate with J2EE and can be used in conjunction with other components. The engine should not require redesign or dramatic changes to existing servlets and JSPs. You should be able to use the engine to add validation to an existing servlet by inserting a few calls at the right place, and handling any problems identified.

Secure by Default

Dang it, validation is a security mechanism. So let's require that the simplest ways of using the engine will be the most secure. If developers want to open it up a bit, that's fine, but they're going to have to do it explicitly. So by default, errors will be fatal and error messages will be generic.

Simple and Obvious API

The API for the validation package should be extremely simple and obvious. I find that in most applications, the best place to set up the rules is very close to the code that sets up the cookies, forms, or headers to be handled. That way, when you change what's acceptable for that page, the rules are right there and easy to modify. Other systems, where you have to set up the rules somewhere else, make it difficult to keep the rules in sync with the contents of the page.

Stinger - A Simple Powerful Validation Engine

There are lots of ways to design an engine that meets these requirements. Let's start this exercise by thinking about a developer using this engine. This is a strange sort of use case, but it will force us to really think about the API. Once we've got an API that we like, we can design the rest of the implementation. So let's try this scenario...

- "Jay is developing a website where users must authenticate to get access to a variety of financial tools. The login page takes a username and password and assigns a session cookie if the login is correct. Each of the financial tools take a variety of user input, including numbers, text, and stock symbols. The tools use the data to query databases, directories, and other systems to generate their responses. Jay wants to make sure that an attacker can't send malicious HTTP requests that will trick his application into doing things it shouldn't"

Imagining that we've defined some rulesets somewhere, it would be nice if Jay could invoke the checks and handle the errors as follows.

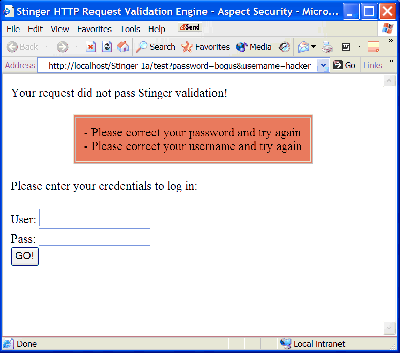

For Jay, all that's left is to set out the rules somehow. Let's try setting the rules for the login page. The username field is required, and there's no point in continuing if it is not correct. The username for Jay's site consists of an 8 digit number. The password field is also required, the only difference is that only alphanumeric characters and underscore are allowed and it must be between 4 and 8 characters in length. A simple XML based format for specifying the rule makes sense. Let's call it Security Validation Description Language (SVDL). Here's how Jay could code the username and password rules. This ruleset uses "/login" for the path, meaning that it will apply to any request that starts with "/login". Note that the password field is marked "hidden" so that the value will not be returned in any automatically generated error message.

To deploy the ruleset, all you have to do is throw this XML file in directory named "rules" directory in the main directory of the webapp. The engine tests whether any files have changed since the last load and reloads them all if any have changed. So you can edit the files and refresh your browser to test whether they're working the way you think they should.

The rest of the site requires a session cookie, so Jay would like to check the validity of the cookie on each of those pages. Note that this doesn't test whether the session id is valid, just whether it has the right format. Let's set this up so that it allows only the JSESSIONID cookie and that it must consist of 32 characters from the set A-F or 0-9. The ruleset ignores "extra" headers or parameters (not defined in this ruleset) and is fatal if it finds any extra cookies or the JSESSIONID cookie is missing. While we're at it, let's have a custom error message if the JESSIONID is malformed.

While we're at it, let's put a few rules on some headers for the entire site. Jay decides to restrict the characters allowed a bit and set the maximum length at 100.

If you're inclined to want JavaScript validation on the client side, Stinger can generate that too. Here's how to include it.

Now with the request validated, Jay can go on and use the information in the HTTP request without additional checking.

An Alpha Stinger Implementation

Under the hood, Stinger is relatively simple. The Stinger singleton maintains a collection of RuleSets that are stored in a Map using the path as a key. Each RuleSet maintains a list of all the Rule objects that have been added to the RuleSet. Each Rule contains a name, type, regular expression, error messages, and all the other information about that particular constraint. When validate() is called, Stinger finds the appropriate RuleSets and applies all the Rules in each one. A FatalValidationException is thrown if a fatal Rule is violated. Otherwise, an ProblemList of ValidationProblems is generated and returned for further processing by the developer.

You can download the alpha implementation of Stinger from the project homepage. All the source code, a test servlet, and a test JSP are included. All you have to do is put stinger-1.0r1.jar and xom-1.0d21.jar on your classpath and you can start using it. Or, if you like, use you can use ant to build Stinger yourself.

Please give me constructive feedback on the design and approach I've described here. And if you have any fairly well tested regular expressions that would be generally useful, I'd love to build them into Stinger.

Stinger 2.0 has since been released. Users are encouraged to download and investigate the latest implementation.