This site is the archived OWASP Foundation Wiki and is no longer accepting Account Requests.

To view the new OWASP Foundation website, please visit https://owasp.org

Cross Site Scripting Flaw

Description

Cross-site scripting (sometimes referred to as XSS) vulnerabilities occur when an attacker uses a web application to send malicious code, generally in the form of a script, to a different end user. These flaws are quite widespread and occur anywhere a web application uses input from a user in the output it generates without validating it.

An attacker can use cross site scripting to send malicious script to an unsuspecting user. The end user’s browser has no way to know that the script should not be trusted, and will execute the script. Because it thinks the script came from a trusted source, the malicious script can access any cookies, session tokens, or other sensitive information retained by your browser and used with that site. These scripts can even rewrite the content of the HTML page.

XSS attacks can generally be categorized into two categories: stored and reflected. Stored attacks are those where the injected code is permanently stored on the target servers, such as in a database, in a message forum, visitor log, comment field, etc. The victim then retrieves the malicious script from the server when it requests the stored information. Reflected attacks are those where the injected code is reflected off the web server, such as in an error message, search result, or any other response that includes some or all of the input sent to the server as part of the request. Reflected attacks are delivered to victims via another route, such as in an e-mail message, or on some other web server. When a user is tricked into clicking on a malicious link or submitting a specially crafted form, the injected code travels to the vulnerable web server, which reflects the attack back to the user’s browser. The browser then executes the code because it came from a ‘trusted’ server.

The consequence of an XSS attack is the same regardless of whether it is stored or reflected. The difference is in how the payload arrives at the server. Do not be fooled into thinking that a “read only” or “brochureware” site is not vulnerable to serious reflected XSS attacks. XSS can cause a variety of problems for the end user that range in severity from an annoyance to complete account compromise. The most severe XSS attacks involve disclosure of the user’s session cookie, allowing an attacker to hijack the user’s session and take over the account. Other damaging attacks include the disclosure of end user files, installation of Trojan horse programs, redirecting the user to some other page or site, and modifying presentation of content. An XSS vulnerability allowing an attacker to modify a press release or news item could affect a company’s stock price or lessen consumer confidence. An XSS vulnerability on a pharmaceutical site could allow an attacker to modify dosage information resulting in an overdose.

Attackers frequently use a variety of methods to encode the malicious portion of the tag, such as using Unicode, so the request is less suspicious looking to the user. There are hundreds of variants of these attacks, including versions that do not even require any < > symbols. For this reason, attempting to “filter out” these scripts is not likely to succeed. Instead we recommend validating input against a rigorous positive specification of what is expected. XSS attacks usually come in the form of embedded JavaScript. However, any embedded active content is a potential source of danger, including: ActiveX (OLE), VBscript, Shockwave, Flash and more.

XSS issues can also be present in the underlying web and application servers as well. Most web and application servers generate simple web pages to display in the case of various errors, such as a 404 ‘page not found’ or a 500 ‘internal server error.’ If these pages reflect back any information from the user’s request, such as the URL they were trying to access, they may be vulnerable to a reflected XSS attack.

The likelihood that a site contains XSS vulnerabilities is extremely high. There are a wide variety of ways to trick web applications into relaying malicious scripts. Developers that attempt to filter out the malicious parts of these requests are very likely to overlook possible attacks or encodings. Finding these flaws is not tremendously difficult for attackers, as all they need is a browser and some time. There are numerous free tools available that help hackers find these flaws as well as carefully craft and inject XSS attacks into a target site.

Environments Affected

All web servers, application servers, and web application environments are susceptible to cross site scripting.

Examples and References

- The Cross Site Scripting FAQ: http://www.cgisecurity.com/articles/xss-faq.shtml

- XSS Cheat Sheet: http://ha.ckers.org/xss.html

- CERT Advisory on Malicious HTML Tags: http://www.cert.org/advisories/CA-2000-02.html

- CERT “Understanding Malicious Content Mitigation” http://www.cert.org/tech_tips/malicious_code_mitigation.html

- Cross-Site Scripting Security Exposure Executive Summary: http://www.microsoft.com/technet/treeview/default.asp?url=/technet/security/topics/ExSumCS.asp

- Understanding the cause and effect of CSS Vulnerabilities: http://www.technicalinfo.net/papers/CSS.html

- OWASP Guide to Building Secure Web Applications and Web Services, Chapter 8: Data Validation http://www.owasp.org/documentation/guide.html

- How to Build an HTTP Request Validation Engine (J2EE validation with Stinger) http://www.owasp.org/columns/jeffwilliams/jeffwilliams2

- Have Your Cake and Eat it Too (.NET validation) http://www.owasp.org/columns/jpoteet/jpoteet2

How to Determine If You Are Vulnerable

XSS flaws can be difficult to identify and remove from a web application. The best way to find flaws is to perform a security review of the code and search for all places where input from an HTTP request could possibly make its way into the HTML output. Note that a variety of different HTML tags can be used to transmit a malicious JavaScript. Nessus, Nikto, and some other available tools can help scan a website for these flaws, but can only scratch the surface. If one part of a website is vulnerable, there is a high likelihood that there are other problems as well.

How to Protect Yourself

The best way to protect a web application from XSS attacks is ensure that your application performs validation of all headers, cookies, query strings, form fields, and hidden fields (i.e., all parameters) against a rigorous specification of what should be allowed. The validation should not attempt to identify active content and remove, filter, or sanitize it. There are too many types of active content and too many ways of encoding it to get around filters for such content. We strongly recommend a ‘positive’ security policy that specifies what is allowed. ‘Negative’ or attack signature based policies are difficult to maintain and are likely to be incomplete.

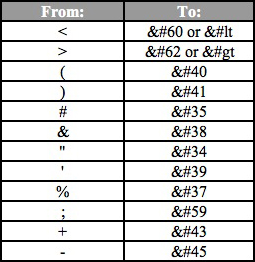

Encoding user supplied output can also defeat XSS vulnerabilities by preventing inserted scripts from being transmitted to users in an executable form. Applications can gain significant protection from javascript based attacks by converting the following characters in all generated output to the appropriate HTML entity encoding:

The OWASP Filters project is producing reusable components in several languages to help prevent many forms of parameter tampering, including the injection of XSS attacks. OWASP has also released CodeSeeker, an application level firewall. In addition, the OWASP WebGoat Project training program has lessons on Cross Site Scripting and data encoding.