This site is the archived OWASP Foundation Wiki and is no longer accepting Account Requests.

To view the new OWASP Foundation website, please visit https://owasp.org

CISO AppSec Guide: Reasons for Investing in Application Security

< Back to the Application Security Guide For CISOs

Part I: Reasons for Investing in Application Security

I-1 Executive Summary

In this digital era, public and private organizations serve an increasing number of citizens, customers and employees through web applications. Often these web applications provide “highly trusted services” over the internet, including functions that bear high risk for the business. These web applications are the target of an ever-increasing number of fraudsters and cyber-criminals. Many incidents result in a denial of online access, breach of customer data and online fraud.

Chief Information Security Officers (CISOs) are tasked to enforce application security measures in order to avoid, mitigate and reduce security risks affecting the organization's ability to deliver on its mission. This evolving threat landscape further drives audit, legal and compliance requirements. CISOs must create a business case for investing in an application security program. The business case should be mapped to the security threats on the business and the program services necessary to serve as a countermeasure. Industry security spending benchmarks and quantitative risk calculations provide support to security investment budget requests.

I-2 Introduction

Applications have grown increasingly critical in organizations. Oftentimes delivering critical services with legal and regulatory requirements. For bank customers, these are feature rich functions that allow them to open bank accounts, pay bills, apply for loans, book resources and services, transfer funds, trade stocks, view account information, download bank statements and others. This online experience is convenient for people: it allows them to perform the same financial transactions as being at the branch/office/outlet, but with the added convenience of conducting these transactions remotely from their home computer or mobile phone. At the same time, this convenience for customers comes at a price to the financial organizations involved in developing and maintaining these applications. For example, online banking and commerce sites have become the target of an increased number of fraudsters and cyber-criminals and victims of security incidents. Several of these incidents resulted in a denial of online access, breaches of data and online fraud.

In the case of data breach incidents, often these attacks from fraudsters and cyber-criminals involve the exploitation of applications such as SQL injection to compromise the data stored in the application database and cross site scripting to execute malicious code such as malware on the user’s browser. The targets of these attacks are both the data and the application business functions for processing this data. In the case of online banking applications, the data targeted by hacking and malware include personal data of individuals, bank account data, credit and debit card data, online credentials such as passwords and PINs and last but not least, alteration of data in on-line financial transactions such as transfers of money to commit fraud. Verizon’s 2012 data breach investigations report identifies hacking and malware as the most prominent types of attack, yielding stolen passwords and credentials, and thus posing a major threat to any organization that trades online.

To cope with this increase of incidents targeting applications, such as denial of services and data breaches often caused by hacking and malware, Chief Information Security Officers (CISOs) have been called by company’s executives such as the Chief Information Officer (CIO), Legal Counsel or Chief Financial Officer (CFO) to build and enforce application security measures to manage application security risks to the organization. For financial organizations for example, the increasing threat to applications such as online banking applications, challenges CISOs to enforce additional application security controls and increase the investment in application security to cope with the increasing risk.

Due to the evolving threat landscape and increased pressure from audit, legal and compliance, in the last decade, investments in application security have been a growing proportion of overall information security and information technology budgets. This trend is also captured in applications security surveys such as the 2009 OWASP Security Spending Benchmarks Project Report that, for example, stated "Despite the economic downturn, over a quarter of respondents expected application security spending to increase in 2009 and 36% expected to remain flat". Furthermore, in the 2013 OWASP CISO Survey, about 87% of respondents indicated that application security investment would either increase or remain constant. Nevertheless, making the business case for increasing the budget for application security today remains a challenge because of the recession economy and prioritization of spending for development of new application features and platforms (e.g. mobile devices), initiatives to expand service uptake or profitability, and marketing to attract new customers and retain existing customers. Ultimately, in today’s recession type of economic climate and in a scenario of slow growth in business investments including the company’s built-in software, it is increasingly important for CISOs to articulate the "business case" for investment in application security. Since it also appears to be a disconnect between organization's perceived threats (application security threats are greatest) yet spending on network and infrastructure security is still much higher, we would like to shed some light on the business impact of data breaches due to application vulnerability exploits and how much these might cost to organizations. Typically, additional budget allocation for application security includes the development of changes in the application to fix the causes of the incident (e.g. fixing vulnerabilities) as well as rolling out additional security measures such as preventive and detective controls for mitigating risks of hacking and malware and limiting the likelihood and impact of future data breach incidents.

CISOs can build a business case for additional budget for application security today for different reasons; some directly tailored to the specific company risk culture or appetite for risk; others tailored to application security needs. Some of these needs can be identified by the analysis of the results of application security surveys. To assess these needs, readers of this guide are invited to participate in the OWASP CISO Survey so that the contents of this guide can be tailored to the needs of CISOs participating in the survey.

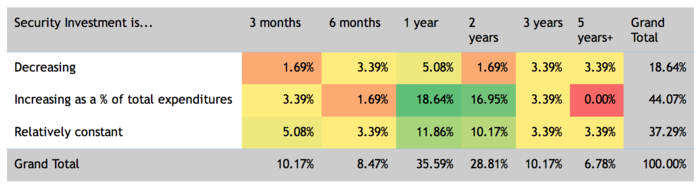

An increased perception of risk of application targeted threats and shifts the organization investment from the traditional network security to application security. In comparison of the application security budget to the company's annual budget:

|

The budgeting for application security measures might depend on different factors such as compliance with security policies and regulations, operational risks management including the risks due to application vulnerabilities and the response of security incidents involving applications. For the sake of this guide we will focus on the following areas to target application security spending:

- Compliance with security standards, security policies and regulations;

- Identification and remediation of application vulnerabilities;

- Implementation of countermeasures against emerging threats targeting applications.

Nevertheless, assuming the business cases can be made along these goals, CISOs today still have the difficult task to determine “how much” money should the company spend for application security and “where” that is on “which security measures” to spend it. Regarding the how much, often it gets down to how much is needed to invest to satisfy compliance requirements and pass the auditor’s check. When the focus is compliance, the focus is to develop and implement application security standards and map these security requirements to current projects. When the focus is vulnerability risk management, the main goal is to fix high risk vulnerabilities and to reduce the residual risk to an acceptable value for the business. When the focus is security incident management, the focus is how to investigate and analyze the suspected security breaches and recommend corrective actions. When the focus is application security awareness, the focus is on institute application security training for the workforce.

For today’s CISO there is an increased focus on making decisions for mitigating risks. Both for mitigating real risks (e.g. incidents, vulnerability exploits) and for mitigating non-compliance risks (e.g. unlawful non-compliance), the question for CISOs is "where" and "how" to prioritize the spending of the application security budget. Often the question is which countermeasure, application security process, activity, or security tool yields “more bang for the money” for the organization. Regarding the "where" it comes down to balance correctly different application security and risk domains - to name the most important ones: business governance, security risk management, operational management that includes network security, identity management, access control and incident management. Since as a discipline, application security encompasses all these domains, it is important to consider all of them and look at the application security investment from different perspectives.

I-3 Information Security Standards, Policies and Compliance

Identifying standards, policies and other mandates in scope for compliance

One of the main factors for funding an application security program is compliance with information security standards, policies and regulations mandated by applicable industry standards regulatory bodies. Initially, it is important for the CISO to define what is in the scope for compliance and how it affects application security. Depending on the industry sector and the geographical location in which the organization operates, there will be several different types of security requirements that the organization needs to comply with. The impact of these requirements is also on the applications that manage and process data whose security falls under the scope of these standards and regulations. The impact on applications consists of performing scheduled risks assessment and to report the status on compliance to the auditors.

Examples of data security and privacy standards that apply to applications in the US include:

- Payment Card Industry (PCI) Data Security Standard (DSS) for payment card merchants and processors

- FFIEC guidelines for US financial organizations whose applications allow clients and consumers to bank online and conduct transactions such as payments and money transfers

- FISMA law for US federal government agencies whose systems and applications need to provide information security for their operations and assets

- HIPAA law for securing privacy of health data whose applications handle patient records in the U.S. healthcare industry

- GLBA law for US financial institutions whose applications collect and store individuals’ personal financial information

- US State Data Breach Disclosure laws for organizations whose applications store and process US state resident Personal Identifiable Information (PII) data when this data is lost or stolen in clear (e.g. un-encrypted)

- FTC privacy rules for organizations whose applications handle private information of consumers in the US as well as when operating in EU countries to comply with “Safe Harbor” rules

OWASP provides several projects and guidance for CISOs to help develop and implement policies, standards and guidelines for application security. Please consult the Appendix B: Quick Reference to OWASP Guides & Projects for more information.

Capturing application security requirements

PCI DSS

Most of the applications that carry out payment transactions such as merchant type of e-commerce applications that handle credit cardholder data are required to comply with the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard PCI-DSS. The requirements for the protection of cardholder data when it is stored by the application includes several PCI DSS requirements such as rendering or encrypting the Primary Account Number (PAN) and masking the PAN when it is displayed. The PCI DSS requirement for card authentication data such as PIN, CVC2/CVV2/CIDs is not to store these data at all, even in encrypted form after a payment has been authorized. Credit cardholder data needs to be protected with encryption when it is transmitted over open networks. These requirements for protection of cardholder personal account numbers and cardholder authentication data motivate the CISO to document internal security requirements to comply with these provisions and to adopt application security measures and assessments to verify that these requirements are met by the applications that are in scope. Besides protection of cardholder data, PCI-DSS has provisions for the development and maintenance of secure systems and applications, for testing security systems and processes and for the testing of applications for common vulnerabilities such as those defined in the OWASP Top Ten.

The need of compliance with the PCI DSS requirements can be a reason to justify an additional investment in technology and services for application security testing: examples include source code security reviews with SAST (Static Analysis Security Testing) assessment/tools and application security reviews with DAST (Dynamic Analysis Security Testing) assessments. For a merchant that develops and maintains a web application such as an e-commerce web site that handles credit card payments, the main question is whether to allocate budget to application security measures and activities to comply with PCI DSS or to incur in fines (e.g. up to $ 500,000 when credit cardholder data is either lost or stolen). From this perspective, unlawful noncompliance with regulations and standards might be treated as another risk by the organization and as any other risk, this could be mitigated, transferred or accepted. If the risk of being non-compliant is accepted, CISO should consider that the data breach risk, because of not implementing basic security controls such as data encryption but also input validation, might be much higher than non-compliance risk.

| T.J.Maxx was non-compliant with PCI DSS when 94 million credit card numbers were compromised in a data breach. Yet, the non-compliance costs for failing to encrypt or truncate card numbers and remediate application vulnerabilities, such as SQL injection, were less of the overall costs incurred by the businesses impacted by this security incident. In the case of T.J Maxx credit card data breach incident, the economical costs incurred by T.J. Maxx because of the incident were a factor of at least a thousand times higher (if not more) than the costs of not compliance with PCI-DSS: several hundreds of millions of US dollars vs. several hundreds of thousands of US dollars. |

FFIEC

In the U.S. banking sector, applications that handle sensitive customer information and are allowed to process financial transactions such as to transfer money between different bank accounts (e.g. electronic wires) must comply with Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) guidelines for online authentication. Requirements include strong authentication such as multi-factor authentication (MFA).

Business drivers for application security investment

Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) requirements for authentication of online banking sites can justify budgeting for application security measures to secure design, implement and test the provision of MFA controls in the application.

GLBA

For US consumers, privacy is regulated under different laws and regulations depending on the industry sectors. In the US financial sectors, laws that govern consumers privacy include GLBA laws and FTC rules. From a GLBA compliance perspective, financial applications need to provide disclosure to application users of which PII is collected, processed and stored and how it is shared among the financial institution businesses and affiliates including third parties. From an FTC compliance perspective, organizations that store consumer PII need to disclose their due diligence security practices to consumers and can be considered liable when such practices are not followed as in the case of a breach of consumer’s private information and in a clear breach of the license agreements with the consumers. Because privacy laws in the US mostly require acknowledging to consumer that the personal data is protected, the impact of security is limited to notifications, acknowledgements and “opt out” controls. Exceptions are cases where privacy controls are implemented as application privacy settings (e.g. as in the case of Facebook), and offered to users of the application as “opt in controls” to comply with the FTC Safe Harbor rules.

Privacy laws

In general, applications that store and process data that is considered personal and private by country specific privacy laws need to protect such data when it is stored or processed. What is considered private information varies country by country. For countries that are part of the European Union (EU) for example, personal data is defined in EU directive 95/46/EC, for the purposes of the directive: Article 2a: "'personal data' shall mean any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person ('data subject'); an identifiable person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identification number or to one or more factors specific to his physical, physiological, mental, economic, cultural or social identity".

For most of the US States, protection of personal identifiable information (PII) is driven by data breach notification laws such as SB1386 where PII is more narrowly defined than in the EU directive as the individual's first name or first initial and last name in combination with any one or more of the following data elements, when either the name or the data elements are not encrypted: (1) Social security number. (2) Driver's license number or State Identification Card number. (3) Account number, credit or debit card number, in combination with any required security code, access code, or password that would permit access to an individual's financial account. For purposes of these laws, "personal information" does not include publicly available information that is lawfully made available to the general public from federal, state, or local government records.

Applications that process and store data that is considered personal private data by EU privacy laws or PII by US States data breach notification laws, need to implement security controls such as authentication, authorization, encryption, logging and auditing to protect the confidentiality, availability and integrity of this data. These information security requirements are typically part of the information security policy enforced by the organization. These security requirements, indirectly translate in security requirements for applications that store and process data that is either considered confidential or confidential PII. Budgeting application security programs for complying with personal and consumer data privacy requirements is justifiable both as internal compliance with information security policy, as well as for mitigating the reputation damage to the organization in the case this data is either lost or compromised. In addition to reputation damage, organizations might incur regulatory fines and legal costs because of non-compliance with local privacy laws.

I-4 Risk Management

Risk management is certainly one of the core CISO functions. The purpose of this section of the guide is to help CISOs in developing, articulating and implementing a risk management process. OWASP also provides documentation guides that can be useful for CISOs to implement a risk management strategy for applications. After reading this section, consult Appendix B for a reference to OWASP guides and projects.

Proactive vs. reactive risk management

Proactive risk management consists of focusing on mitigating the risks of threat events before these might possibly occur and negatively impact the organization. Organizations, whose focus is proactive risk management, plan to protect mission critical assets including applications ahead of potential threats targeting them. Proactive risk mitigation activities for applications include focusing on threat intelligence to learn about threat agents, application threat modeling to learn how the application can be protected by attacks from different threat agents, security testing and fixing of potential vulnerabilities in the application as well as in the source code before these are exploited by potential attackers. A pre-requisite for proactive risk management is to have an inventory of the mission critical applications with associated risk profiles that allow CISOs to identify the critical digital assets such as data and functions that need to be prioritized and planned for proactive risk mitigation activities. CISOs whose organizations focus on proactive risk mitigation measures have typically adopted a risk mitigation strategy and act upon information from threat intelligence and monitored security events and alerts to raise the bar on acceptable technical and business risks. CISOs whose focus is proactive risk mitigation usually require the roll out of additional countermeasures ahead of new threats and new compliance requirements.

Reactive risk management consists of responding to risk events as they occur to mitigate negative impacts to the organization. Examples of reactive risk management activities include security incident response, security incident investigations and forensics and fraud management. In the case of application security, reactive risk management activities include vulnerability patch management, fixing application vulnerabilities in response to reported security incidents or when these are identified by third parties, performing application risk assessment due to occasional (not planned) requirements to satisfy specific compliance and audit requirements. CISOs whose organizations focus on reactive risk management typically spend more focus on responding to unplanned risk management events. Often the focus of reactive risk management is "damage containment" to “stop the bleeding” and less focus is dedicated to planning for risk mitigation ahead of potential negative events targeting applications. Typically organizations whose focus is on reactive risk management have their CISOs spending most of their time on incident response and management and remediating application vulnerabilities either ahead of production releases or patching applications that are already released in production. When the prime focus of the CISO function is on reactive risk management, it is important to recognize that reactive risk mitigation, even if it cannot always be avoided because security incidents happen, is not cost effective since the cost of remediating issues after they have been either reported or exploited by an attacker is several factors of magnitude higher than identifying and fixing the same by adopting preventive risk mitigation measures.

A proactive risk mitigation approach is preferable to a reactive risk mitigation approach when making the business case for application security. A proactive risk mitigation approach might consist on using the opportunity of a required technology upgrade of a application to introduce new functionality or when an old application reaches end of life, and needs to migrate to a newer system/platform. Designing new features to applications represents an opportunity for CISOs to demand upgrade security technology to new standards and implement stronger security measures as well.

Asset centric risk management

CISOs whose information security policies are derived for compliance with information security standards such as ISO 17799/ISO 27001 include asset management as one of the security domains that need to be covered. In the case when these assets include the applications, assets management requires an inventory of the applications that are managed by the organization in order to implement a risk management approach. This inventory includes information on the type of applications, the risk profile for each application, the type of data that is stored and processed, patching requirements and the security assessments such as vulnerability testing that are required. This inventory of applications is also critical to track application security assessments and risk management processes conducted on the application, the vulnerabilities that have been identified and fixed as well as the ones that are still open for remediation. The risk profile that is assigned to each application can also be stored in the application inventory tool: depending on the inherent risk of the application that depends on the classification of the data and the type of functions that the application provides, it is possible to plan for risk management and the prioritization of the mitigation of existing vulnerabilities as well as for the planning for future vulnerability assessments and application security assessment activities. One of the application security activities that take advantage of asset centric risk management is application threat modeling. From an architecture perspective, assets consist of several components such as application servers, application software, databases and sensitive. Through application threat modeling, it is possible to identify threats and countermeasures for the threats affecting each asset. CISOs whose focus is on asset risk management, should consider implementing application threat modeling as proactive application security and asset centric risk management activity.

Technical vs. business risk management

When deciding how to mitigating the application security risks it is important to make the trade off between technical risks and business risks. Technical risks are the risks of either technical vulnerabilities or control gaps in an application whose exploit might cause a technical impact such as lost and compromised data, server/host compromise, unauthorized access to an application data and functions, denial or disruption of service as examples. Technical risks can be measured as the impact of confidentiality, integrity and availability of the asset caused by a technical event/cause such as vulnerability that is identified by an application security assessment. The managing of these technical risks typically depends on the type of the vulnerability and the risk rating assigned to it, also referred to as "severity" of the vulnerability. The severity of the vulnerability can be calculated based upon risk scoring methods such as FIRST's CVSS, while the type of vulnerability can be classified based upon the group that the vulnerability falls into such as using MITRE's CWE. CISOs can use the risk scoring of a vulnerability reported as HIGH, for example, to prioritize such vulnerability for mitigation ahead of vulnerabilities that are scored as MEDIUM or LOW risk. In making this technical vulnerability risk management decision, CISO won’t consider the economical impact of the vulnerability to the business, such as in the case the value of the asset impacted by the vulnerability is either lost or compromised.

Business risk management occurs when the value of the asset is taken into account to determine the impact to the organization. This requires the association of technical risk of the vulnerability with the asset value to quantify the risk. The risk can be factored as the likelihood of the asset being compromised and the business impact caused by the exploit of the vulnerability. For example, in the case that a high risk technical vulnerability such as SQL injection (assumed is fully, 100% exposed as a pre-authentication issue) is exploited, the business impact can be determined as impact to an asset, such as data, that is classified as sensitive data and whose value if compromised is estimated as $ 250/data record (e.g. based upon either internal incident cost estimates or publicly reported estimates). The aggregated value of the sensitive data of 100,000 records stored in a database that could be exploited by SQL injection is therefore $ 25 Million. If the probability of a sensitive data compromise due to the exploit of SQL injection vulnerability is estimated as 10 % (1 successful data breach incident caused by SQL injection every ten years) the potential economical impact is a loss of $ 2,500,000. Based upon these estimates, it is possible to calculate how much to budget in application security measures (e.g. detective and preventive controls) for mitigating the risks to the business.

It should be noted that estimating business risks is much more difficult than estimating technical risks since business risk estimates require estimates of the likelihood of specific types of security incidents (e.g. data breaches) as well as the estimates of the monetary losses (e.g. loss of revenue, legal-compliance costs, incident cause repair costs) caused by that incident. Typically these estimates are not easy to make in absence of specific data and calculation tools that can factor the frequency of security data breach incidents and keep records of direct and indirect costs suffered by the organization as a result of these security incidents. Nevertheless, statistical data of data breach incidents, estimates of the costs of data breach incidents as well as data breach quantitative risk calculators might help. The Appendix A Value Data & Costs of an Incident provides examples, formulations and online calculators to help CISOs assigning monetary value to information assets and determine the monetary impact for the organization in the case where such assets will be lost because of a security incident. The purpose of these quantitative risk calculations is to help CISOs decide how much is reasonable to spend in application security measures to reduce the business impacts for the organization in the case of data breach incident.

Risk management strategies

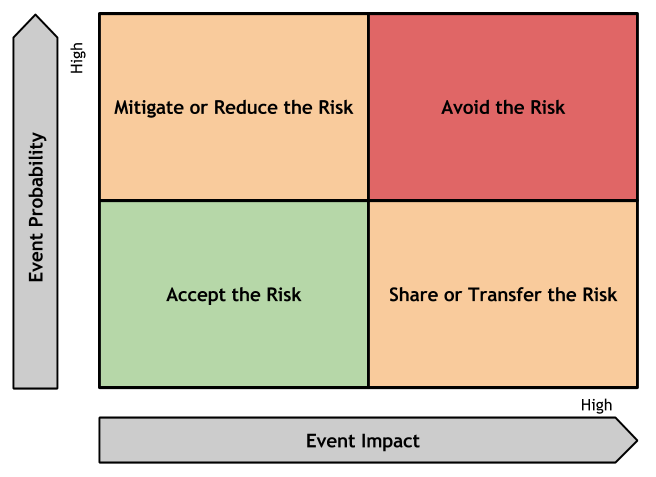

Once security risks have been identified and assigned a qualitative value such as high, medium and low risk, the next step for the CISO is to determine what to do with that risk. To decide “what to do with the risks” CISOs usually rely upon their organization's risk management processes and risk mitigation strategy. Risk management processes are usually different for each type of organization. At high level, risk management depends on the risk mitigation strategy that is adopted by the organization. Depending on the assessment of the level of risk impact and probability, for example, an organization might decide to accept the risks whose likelihood and impact are low, mitigate or reduce the risks (e.g. by applying security measures) that have high probability and low impact, transfer or share the risks (e.g. to/with a third party such as through contractual agreements) that are of low probability and high impact and avoid the risks (e.g. such as not to implement high risk functions, not to adopt high risk technologies) that have high probability and impact. A visual example of this risk mitigation strategy factored by event likelihood and impact is shown in the diagram below.

In the case high risks cannot be avoided because of business decisions requiring to mitigate them, and risks cannot be transferred to third parties through contractual agreements and cyber insurance, a possible risk strategy for the organization could be to mitigate all risks that are medium and high and accept (e.g. do nothing) only the ones whose residual risk (e.g. the risk left after either measures or compensating control are either applied or considered) are low. Risk mitigation strategies can also factor business risks using qualitative risk analysis that factor risks such as probability and economical impacts. Once the risk has been determined, the next step is to decide which risk the organization is willing to accept, mitigate, transfer or to avoid. For the risks that the organization is willing to accept it is important for CISOs to have a risk acceptance process that qualifies the low level of risk based upon the presence of compensating controls and that can be signed off by him and executive management. For the risks that are chosen for risk mitigation, it is important to determine which security measures/corrective actions are deemed acceptable by the organization and to decide which of these measures are most effective in reducing risks by minimizing the costs (e.g. highest benefit vs. minimum security measure total costs). This is where the risk mitigation strategy needs to consider the cost of potential security incidents, such as data breaches, to decide how much is reasonable for the organization to budget for investments in application security measures. An important aspect of the risk strategy for CISOs is to decide which security measures work best together as "pluribus unum" that includes applying preventive and detective controls to provide a defence in depth of the application's assets. Finally, for the risks that are either transferred or shared with a third party, it is important for the CISO to work with legal to make sure risk-liability clauses are documented in the legal agreements and service license agreements are signed by the organization with the third party service provider/legal entity.

Threat analysis and awareness of emerging threats

Making the business case for additional spending on application security measures is not always justifiable without risk data from the analysis of the impact of emerging threats and the increased level of risks that needs to be mitigated. Threat analysis data allow informed risk management decisions. In the absence of such data, the management is left with subjective considerations about threats.

Subjective considerations about threats are most often decisions based upon Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt (FUD). Acting upon FUD to mitigate risks posed by emerging threats is late-coming and ineffective. Example actions based on FUD include, but are not limited to:

- Fear of data breaches

- Fear of failing audit and compliance

- Uncertainty regarding business threats

- Doubts about effectiveness of existing security measures in light of recent security incidents

The intent of this part of the guide, is to help CISOs to create an additional business case for application security investment based upon objective threat analysis instead of subjective considerations. From a compliance with standards perspective, objective considerations are based upon a rationale for investing in applications security that includes complying with new security standards and regulations that impact applications. From a threat analysis perspective, objective considerations are based upon data regarding the business impact of emerging threat agents seeking to compromise applications for financial gain. Specifically regarding making the case for mitigation of risks, it is necessary for CISOs to avoid assumptions and back the case with data such as reports and analysis of cyber-threats and security incidents, costs of data breaches to estimate liability and quantitative calculations of risk based upon estimates of probability and impacts. Based upon risk calculations and data breach cost estimates, it is possible for the CISO to articulate how much the organization should invest in application security and to determine in which specific measures to invest.

From a fear perspective it is true that CISOs can also exploit the momentum, being this either a negative or positive event, but this is part of a reactive risk management approach and low maturity in dealing with risks. Often application security spending can be triggered by a negative event such as a security incident, since this shifts senior management's perception of risk. However, CISOs should find that using a one to two year roadmap to drive security investment would be more effective as found in the 2013 OWASP CISO Survey.

In this case, the money is probably already being spent to limit the damage, such as to remediate the incident and implement additional countermeasures. The main question then is what further investment in application security will reduce the likelihood and impact of another similar incident happening in the future. One approach is to focus on applications that might become a target for future attacks.

Addressing the business concerns after a security incident

The implementation of a security incident response process is an essential activity for every CISO. Such security incident response process requires the identification of a point of contact for security issues, the adoption of a security issue disclosure process and the creation of an informal security response team(s). In the case of a security incident, CISOs are often tasked to conduct root cause analysis for incidents, collect per-incident metrics and recommend corrective actions. In Appendix B we provide CISOS with a quick reference to OWASP guides & projects to help CISOs investigating and analyzing suspected and actual application security incidents and recommend corrective actions.

Once the root causes of the incident have been identified and corrective actions have been taken to contain the impact of the security incident, the main question for CISOs is what should be done to prevent similar security incidents to occur in the future. If an application has been targeted by an attack and sensitive data was either lost or compromised the main question is to whether similar applications and software might be also at risk of similar attacks and incidents in the future. The main question for the CISO is which application security measures and activities should be targeted for spending to mitigate the risks of breaches of sensitive data due to malware and hacking attacks to applications and software that are developed and managed by the organization.

After these measures are selected, the next question is how much should be spent in countermeasures. From the costs vs. benefit perspective, application security spending matching all of the costs of the business impact of a possible data breach is not justifiable since it will cost the business as much as doing nothing hence with no risk benefit for investing in countermeasures. The main question for the CISOs is therefore how much should be spent to reduce the risk of a data breach incident at a fraction of the cost of implementing a security measure: if not 100%, is it 50%, 25% or 10% of all possible monetary losses? Also, how will I estimate the monetary losses of a security incident? Which methods should I use? Does the loss estimate include non-monetary losses such as reputation loss?

The goals of the following sections of the guide are to help CISOs in budgeting of application security measures for mitigating risks of data breach incidents by analyzing the risks of data breach incidents, monetizing the economical impacts and estimating the likelihood and the business impacts. Only after this "risk due diligence" work is done is it possible to determine the costs and compare with the risk mitigation benefits and decide in which security measures to invest. In Appendix A of this guide we provide a quick reference to assign monetary value to information assets and to determine the monetary impact of a security incident based upon statistical data. After measures are implemented it is important to measure and monitor security and the risks. In Appendix B we provide examples of OWASP projects that can help the CISO to measure and monitor security and risks of application assets within the organization.

Budgeting of application security measures for mitigating risks of data breach incidents

For guiding the CISOs in making decisions on "how much money the organization needs to budget for application security" we will focus on risk mitigation criteria rather than other factors such as percentage of the overall Information Technology (IT) budget and year over year budget allocation for applications security as a fraction of overall information security budget that includes compliance and operational-governance costs. A risk based application security budgeting criteria documented in this guide consist of the following:

- Estimate of the impact of the costs incurred in the event of an security incident

- Quantitative risk calculation of the annual cost for losses due to a security incident

- Optimization of the security costs in relation to cost of incidents and cost of security measures

- The return of security investment in application security measures

We shall explain in the following sections of this guide each of these criteria and how they can be used for quantifying how much money to spend on application security measures.

Analyzing the risks of data breach incidents

There are two important factors to determine the risk of a security incident: these are the negative impact caused by the security incident and the likelihood (probability) of the incident. To obtain an estimate of the impact of the costs incurred in the event of a security incident, the key factor is the ability to ascertain the costs incurred due to the security incident. Examples of negative impacts to an organization because of a security incident might include:

- Reputation loss such as, in the case of publicly traded company, a drop in stock price as consequence of announced security breach;

- Loss of revenue such as in the case of denial of service to a site that sells services or goods to clients and customers;

- Loss of data that is considered an asset for the company such as users' confidential data, Personal Identifiable Information (PII), authentication data, and trading secrets/intellectual property data;

- Inability to deliver a statutory service to citizens;

- Adverse impact on individuals whose data has been exposed.

Monetizing the economical impacts of data breach incidents

In the case of a security incident that caused a loss of sensitive customer or employee data such as personal identifiable information, debit and credit card data, the costs incurred by the organization that suffered the loss include several operational costs also referred as failure costs. In the case of a financial services company, these are the costs for changing account numbers, remission costs for issuance of new credit and debit cards, liability costs because of fraud committed by the fraudster using the stolen data such as for illicit payment transactions and withdrawal of money from ATMs. Often times, the determination of such “failure” costs is not directly quantifiable by an organization, such as when this monetary loss is not directly caused by a security incident, hence ought to be estimated as a possible impact. In this case, CISOs can use statistical data to determine the possible liability costs to the company in case of data loss incident. By using reported statistical data from data loss incidents, it is possible to estimate the costs incurred by companies to repair the damage caused by a security incident that resulted in losses of sensitive data or identity loss.

The value of data will be different for each organization, but values in the range of $500 to $2,000 per record seem to be common.

Data value: $200 to $2,000 per record

We will use this range for the remaining discussion, but each CISO needs to come up with some valuation of their own that can then be used to calculate the impact of a data loss.

Note: Appendix A Value of Data & Cost of an Incident contains a detailed discussion, examples and a data breach calculation tool to estimate the cost of a data breach based upon statistical data.

Estimating the likelihood of data breach incidents

One of the challenges of the calculation of the burden to the company because of a potential data loss is to get an accurate estimate of the amount of the loss x victim and of the probability or likelihood of such loss occurring. Statistical data about reported data loss incidents to breach notification letters sent to various jurisdictions in the United States collected by the Open Security Foundation's (OSF) DataLossDB show that the percentage of 2010 data loss incidents breaching a web interface is 9% and the percentage that reported as being a hack is 12%, fraud 10% and virus 2%. The highest reported incident by breach type is stolen laptop with 13% of all reported incidents.

The data from OSF DataLossDB related to web as type of breach differ from the statistics of the Verizon’s 2011 data breach investigations report where hacking (e.g. brute force, credential guessing) and malware (e.g. backdoors, keyloggers/form grabbers, spyware) represent the majority of threats for security breaches (50% and 49% respectively) and attacks against applications represent 22% of all attack vectors and 38% as percent of records being breached.

These differences might be explained by the fact that the Verizon study is based upon a subset of data from the U.S Secret Service and does not include, for example, cases related to theft and fraud that are instead counted on the overall OSF DataLoss DB statistical data. Furthermore, according to the Verizon report; "the scope of the survey was narrowed to only those involving confirmed organizational data breaches". In the case of OSF, survey data includes data breaches covered by U.S State data breach notification law such as when resulting in disclosure of customer's Personal Identifiable Information (PII) and reported by organizations with notification letters sent to various jurisdictions in the United States.

Quantification of the business impact of data breach incidents

In the cases when the impact of an occurred data breach due to a security incident are not being recorded and notified to the public in compliance with the data breach notification laws enforced by different countries and jurisdictions, it is necessary to estimate it based upon risk estimate calculations. Besides the calculation of liability costs based upon the value of data (refer to Appendix A Value of Data & Cost of an Incident for estimate the value of data), quantitative risk analysis can be used to estimate the spending for application security measures on the yearly basis such as by calculating the impact of a security incident on an annual basis. Quantitative risks can be calculated by the assessment of the Single Loss Expectancy (SLE) or probability of a loss as a result of a security incident and the Annual Rate of Occurrence (ARO) or the annual frequency of the security incident. By using quantitative risk analysis and using publicly available reports of data breaches, CISOs can estimate the amount that a given organization managing an application would loose and therefore should spend on application security measures to mitigate the risk of a data loss due to the exploitation of an application vulnerability. The accuracy of this risk estimate depends on how reliable and pertinent the data breach incident is to application security. It is therefore important to choose the data carefully as this is being reported as being caused by an exploit of application vulnerabilities such as SQL injection (e.g. Sony and TJX Max data breaches).

The SLE can be calculated with the following formula:

SLE = AV x EF

Where, AV is the Asset Value (AV) and EF is the Exposure Factor (EF). The EF represents the percentage of the asset loss because of the realization of a threat or an incident. In the case of the 2003 US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) incident data this represents the amount of the population that suffered identity fraud and is 4.6%.

Assuming the AV of 1 million accounts of $ 655,000,000 ( $655 per account based upon 2003 FTC data) and an exposure factor of 4.6%, the estimated SLE of the data breach incident is $ 30,130,000. Assuming a frequency of 1 attack every 5 years such as in the case of TJX Inc data breach incident (discovered in mid-December 2006 and due to SQL injection exploits) the ARO is 20%. Hence the estimated annual loss or Annual Loss Expectancy (ALE) can be calculated using the formula:

ALE = ARO x SLO

The calculated Annual Loss Expectancy (ALE) for data loss incident is therefore $ 6,026,000/year over 10 years.

Considering costs and benefits of application security measures before making investments

Now the question is if using quantitative risk analysis leads to an estimate of the optimal investment for application security measures. The honest answer is, not necessarily. The correct answer is to use cost vs. benefit analysis to determine the optimal value. By comparing the costs of security incidents against the costs of security measures, it is possible to determine when this maximizes the benefit, that is, the overall security of the application.

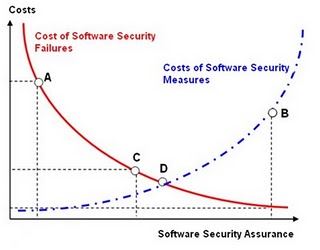

In the case of software security costs for example, the cost due to software security failures including security incidents decreases as the company spends more money in security measures as shown in (FIG 1). The assumption is that an increased investment in security measures translates to less risk and a reduced impact for the business. This is based on the assumption that risks are decreasing when investments in security are increasing. The other assumption is that investments are directed toward effective risk mitigation security measures. To decide which security measures are risk mitigation effective and should be invested in, it is implied that CISOs have done a risk analysis to identify the most cost effective security measures (e.g. processes, technical controls, tools, training and awareness etc.) and selected the ones that reduce the risk the most and cost the least to implement, deploy and maintain. Note: this might not always be true as more spending in security measures does not always translate into increased risk mitigation: for example spending more on anti-virus protection won't reduce the risk of malware compromise as malware is designed to evade virus signature detection systems.

It is of the upmost importance to consider the effectiveness of security measures in mitigating the possible impact of specific threats before deciding if it is cost effective to invest in them. In part II of this guide we provide guidance to help CISOs identify which vulnerabilities should be prioritized for fixing and which security measures are most effective in mitigating specific threats targeting web applications. Before making decisions on which security measures to invest please consult Part II "Criteria for Managing Application Security Risks".

With these assumptions, the more money spent on security measures to prevent security incidents the less money will be lost in a security incident when this occurs; such as costs to recover from security incident, fix vulnerabilities, implement new measures and paying for regulatory fines, contract liability costs and legal costs. The assumption is that, because of an increase in spending in protective and detective security controls, testing and fixing vulnerabilities and other measures, security incidents will be less likely to occur and when they occur will have a reduced impact for the organization. In the case of applications, the implementation of security measures falls under the scope of the application security program. CISOs can look at Part III "Application Security Program" of this guide to learn which security processes, tools and training should be considered prior to investing in application security measures.

With these caveats, as more money is spent in application security a point could be reached when the costs outweigh the benefits. This is obviously not the objective of risk management and a limit that should not be reached if possible as this will undermine the whole risk mitigation strategy and put pressure on CISOs to justify their budgets. A sound risk mitigation strategy is rather the one that seeks to identify at which value of security investment the benefits for the business will be maximized while the impacts will be minimized. This value is the optimal value of investment in security measures and can be estimated by measuring the costs incurred because of security incidents as well as the investment in security measures. By assuming that such cost measurement metrics have been adopted by the organization, it would be possible to determine if an increase of budget in mitigating the risks correlates with a reduced number of security incidents and reduced overall impact caused by these security incidents. In Part IV of this guide we provide guidance to CISO for establishing "Metrics for Managing Risks & Application Security Investments". In absence of such metrics to determine the optimal value of application security investments, CISOs can look at some research studies that point to the optimal investment when the cost of security measures is approximately 37% of the estimated losses. For our example, assuming the total estimated losses of $ 6,026,000/year due to data loss incidents, the optimal expense for security measures, using this empirical value from the study, is $ 2,229,620/year.

Cost of Investment in software security measures against failure costs due to incidents that exploit software vulnerabilities. At the point (A) the costs due to software security failures exceed of several order of magnitude the expenditure in countermeasures and the assurance on the security of the software is very low, on the contrary in (B) the costs of security measures outweigh the costs due to the software failures, the software can be considered very secure but too much money is spent for software security assurance. In point (C) the cost of losses is nearly two times larger costs of security measures while in point (D) the costs due to incidents is equal to the cost of the security measures. The optimal value for spending of security measures is the one that minimizes both the cost of incidents and security measures and maximizes the benefit or the security of the software.

Analyzing security measures as investments

For most organizations today’s application security is not seen as an investment but as a cost imposed by necessity to comply with standards and regulations. Some organizations might justify spending on application security because of risk management requirements, others because of increased awareness of the exposure to threats from cyber criminals, fraudsters and hacktivists. Some organizations might consider the cost saving that investment in security provides as shorter "time to market" as they will release a security product earlier than the competition. Some organizations might realize that spending in security for web applications might increase the level of trustworthiness that customers have in the web applications they are accustomed to use and help retain these customer business as well as sell them more services: these organizations might see spending on application security in a positive light as an investment and not as a cost. For organizations that consider security as investment and not as a cost, it is important to determine the most efficient way to spend the application security budget from the perspective of this being an investment. If the CISO considers application security spending as an investment rather than an expense, for example, the budget can be justifiable as additional savings the company gets because of less money spent on dealing with security incidents.

An example of this "money saving thinking" could be "if I spend a total of $$ in security measures to prevent security incidents in the next two years I will save a total of $$ in possible losses, fixing vulnerabilities and other direct and indirect costs caused by an estimated number of security incidents in the next two years". One of the methods to calculate the savings in terms of investment in security is the Return on Security Investment (ROSI). The use of ROSI can help CISOs to determine if the investment in countermeasures to thwart specific cyber-attacks is justifiable as a long term security investment: if the ROSI is not positive, the investment is not justifiable while if it is null, it does not yield any savings or investment returns.

There are several empirical formulas to calculate ROSI; one is to factor the savings for the data losses avoided over the total cost of the security controls/measures. Assuming the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) for the cost of security control/measure is $ 2,229,620 (previously calculated as optimal value of expense in security controls for SQL injection mitigation per year) that includes development costs and acquisition of the new technologies, processes, tools as well as operating and maintenance costs, it is possible to calculate the savings in security incident costs. The ROSI can be calculated using the following empirical formula:

ROSI = [(ALE x % of control effectiveness) - cost of controls]/cost of controls

With this ROSI formula, assuming a pre calculated ALE (Annual Loss Expectancy) for security incidents caused by exploit of SQL injection vulnerabilities is $ 6,026,000 and that the effectiveness of the risk control mitigation is 75% (e.g. assume for example, in the case of a SQL injection, risk mitigation as defence in depth such as different layers of controls that include use of prepared statements/stored procedures in source code as well as filtering of malicious characters at the web server and application server), the cost of security controls is $ 2,229,620, the ROSI to the company is 102% per year. With this value of return of security investment, the spending in security control measures is worth it and will make the company save money each year. The best use of ROSI is to compare alternative investments in security measures such as to decide whether to invest in the development of a new countermeasure or extending the capabilities of an existing one.

As a comparative measurement for example, ROSI can be used by CISOs to determine which application security process is more efficient or yields the organization the higher savings and returns on the investment during the life-span of a Software Development Life-Cycle (SDLC). According to research of Soo Hoo (IBM) of the ROSI of the various security activities in the SDLC, the maximum return of investment (21%) (e.g. a savings of $ 210,000 on an investment of a $ 1 Million in Secure Software Development Lifecycle (S-SDLC) program) is when most of the money is invested in activities that can identify and allow to remediate security defects during the design phase of the SDLC such as architectural risk analysis and application threat modeling. The return of investment is lower (at 15%) when the defects are identified and remedied during the implementation (code) phase of the SDLC such as with source code analysis and even lower (at 12%) when these are identified and remedied during the testing-validation phase of the SDLC such as with ethical hacking/pen tests. By using the ROSI as comparative metrics for investments for SSDLC activities, the most cost effective investment in application security is therefore in activities that can identify defects as early as possible, such as requirements and design phase of the SDLC. In essence, the more CISOs think about investing in application security programs and especially security requirement engineering activities such as threat modeling/architectural risk analysis activities and secure code reviews the more they'll save on the costs of implementing and fixing security issues with other activities such as penetration testing.

Conclusion

Finally, it is important to notice that the cost estimates using the risk and cost empirical formulas dealt in this guide are as good as the reliability of data values that are used. The more accurate are these data values the more accurate are the cost estimates. Nevertheless, when these risk-cost criteria are used consistently and based upon tested quantitative risk calculations and reliable data can be used by CISO for objective risk and cost considerations to decide if the investment in application security measures is financially justifiable. These risk and cost considerations can also be used by CISOs to either defend their budgets in light of cost cutting measures or ask for more budget. Today an increased budget in application security can be justified in light of the increased exposure of web applications to the risk and monetary losses caused by security incidents. Since investment in application security has to be justified in business terms, these risk-cost criteria can be used for business cases as well as to decide how much to spend and where to spend in application security measures.