This site is the archived OWASP Foundation Wiki and is no longer accepting Account Requests.

To view the new OWASP Foundation website, please visit https://owasp.org

Fingerprint Web Server (OTG-INFO-002)

This article is part of the new OWASP Testing Guide v4.

Back to the OWASP Testing Guide v4 ToC: https://www.owasp.org/index.php/OWASP_Testing_Guide_v4_Table_of_Contents Back to the OWASP Testing Guide Project: https://www.owasp.org/index.php/OWASP_Testing_Project

Summary

Web server fingerprinting is a critical task for the Penetration tester. Knowing the version and type of a running web server allows testers to determine known vulnerabilities and the appropriate exploits to use during testing.

There are several different vendors and versions of web servers on the market today. Knowing the type of web server that you are testing significantly helps in the testing process, and will also change the course of the test. This information can be derived by sending the web server specific commands and analyzing the output, as each version of web server software may respond differently to these commands. By knowing how each type of web server responds to specific commands and keeping this information in a web server fingerprint database, a penetration tester can send these commands to the web server, analyze the response, and compare it to the database of known signatures. Please note that it usually takes several different commands to accurately identify the web server, as different versions may react similarly to the same command. Rarely, however, different versions react the same to all HTTP commands. So, by sending several different commands, you increase the accuracy of your guess.

Test Objectives

How to Test

Black Box testing and example

The simplest and most basic form of identifying a Web server is to look at the Server field in the HTTP response header. For our experiments we use netcat. Consider the following HTTP Request-Response:

$ nc 202.41.76.251 80 HEAD / HTTP/1.0 HTTP/1.1 200 OK Date: Mon, 16 Jun 2003 02:53:29 GMT Server: Apache/1.3.3 (Unix) (Red Hat/Linux) Last-Modified: Wed, 07 Oct 1998 11:18:14 GMT ETag: "1813-49b-361b4df6" Accept-Ranges: bytes Content-Length: 1179 Connection: close Content-Type: text/html

From the Server field, we understand that the server is likely Apache, version 1.3.3, running on Linux operating system.

Four examples of the HTTP response headers are shown below.

From an Apache 1.3.23 server:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK Date: Sun, 15 Jun 2003 17:10: 49 GMT Server: Apache/1.3.23 Last-Modified: Thu, 27 Feb 2003 03:48: 19 GMT ETag: 32417-c4-3e5d8a83 Accept-Ranges: bytes Content-Length: 196 Connection: close Content-Type: text/HTML

From a Microsoft IIS 5.0 server:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK Server: Microsoft-IIS/5.0 Expires: Yours, 17 Jun 2003 01:41: 33 GMT Date: Mon, 16 Jun 2003 01:41: 33 GMT Content-Type: text/HTML Accept-Ranges: bytes Last-Modified: Wed, 28 May 2003 15:32: 21 GMT ETag: b0aac0542e25c31: 89d Content-Length: 7369

From a Netscape Enterprise 4.1 server:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK Server: Netscape-Enterprise/4.1 Date: Mon, 16 Jun 2003 06:19: 04 GMT Content-type: text/HTML Last-modified: Wed, 31 Jul 2002 15:37: 56 GMT Content-length: 57 Accept-ranges: bytes Connection: close

From a SunONE 6.1 server:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK Server: Sun-ONE-Web-Server/6.1 Date: Tue, 16 Jan 2007 14:53:45 GMT Content-length: 1186 Content-type: text/html Date: Tue, 16 Jan 2007 14:50:31 GMT Last-Modified: Wed, 10 Jan 2007 09:58:26 GMT Accept-Ranges: bytes Connection: close

However, this testing methodology is limited in accuracy. There are several techniques that allow a web site to obfuscate or to modify the server banner string. For example we could obtain the following answer:

403 HTTP/1.1 Forbidden Date: Mon, 16 Jun 2003 02:41: 27 GMT Server: Unknown-Webserver/1.0 Connection: close Content-Type: text/HTML; charset=iso-8859-1

In this case, the server field of that response is obfuscated: we cannot know what type of web server is running based on such information.

Protocol behaviour

More refined techniques take in consideration various characteristics of the several web servers available on the market. We will list some methodologies that allow us to deduce the type of web server in use.

HTTP header field ordering

The first method consists of observing the ordering of the several headers in the response. Every web server has an inner ordering of the header. We consider the following answers as an example:

Response from Apache 1.3.23

$ nc apache.example.com 80 HEAD / HTTP/1.0 HTTP/1.1 200 OK Date: Sun, 15 Jun 2003 17:10: 49 GMT Server: Apache/1.3.23 Last-Modified: Thu, 27 Feb 2003 03:48: 19 GMT ETag: 32417-c4-3e5d8a83 Accept-Ranges: bytes Content-Length: 196 Connection: close Content-Type: text/HTML

Response from IIS 5.0

$ nc iis.example.com 80 HEAD / HTTP/1.0 HTTP/1.1 200 OK Server: Microsoft-IIS/5.0 Content-Location: http://iis.example.com/Default.htm Date: Fri, 01 Jan 1999 20:13: 52 GMT Content-Type: text/HTML Accept-Ranges: bytes Last-Modified: Fri, 01 Jan 1999 20:13: 52 GMT ETag: W/e0d362a4c335be1: ae1 Content-Length: 133

Response from Netscape Enterprise 4.1

$ nc netscape.example.com 80 HEAD / HTTP/1.0 HTTP/1.1 200 OK Server: Netscape-Enterprise/4.1 Date: Mon, 16 Jun 2003 06:01: 40 GMT Content-type: text/HTML Last-modified: Wed, 31 Jul 2002 15:37: 56 GMT Content-length: 57 Accept-ranges: bytes Connection: close

Response from a SunONE 6.1

$ nc sunone.example.com 80 HEAD / HTTP/1.0 HTTP/1.1 200 OK Server: Sun-ONE-Web-Server/6.1 Date: Tue, 16 Jan 2007 15:23:37 GMT Content-length: 0 Content-type: text/html Date: Tue, 16 Jan 2007 15:20:26 GMT Last-Modified: Wed, 10 Jan 2007 09:58:26 GMT Connection: close

We can notice that the ordering of the Date field and the Server field differs between Apache, Netscape Enterprise, and IIS.

Malformed requests test

Another useful test to execute involves sending malformed requests or requests of nonexistent pages to the server. Consider the following HTTP responses.

Response from Apache 1.3.23

$ nc apache.example.com 80 GET / HTTP/3.0 HTTP/1.1 400 Bad Request Date: Sun, 15 Jun 2003 17:12: 37 GMT Server: Apache/1.3.23 Connection: close Transfer: chunked Content-Type: text/HTML; charset=iso-8859-1

Response from IIS 5.0

$ nc iis.example.com 80 GET / HTTP/3.0 HTTP/1.1 200 OK Server: Microsoft-IIS/5.0 Content-Location: http://iis.example.com/Default.htm Date: Fri, 01 Jan 1999 20:14: 02 GMT Content-Type: text/HTML Accept-Ranges: bytes Last-Modified: Fri, 01 Jan 1999 20:14: 02 GMT ETag: W/e0d362a4c335be1: ae1 Content-Length: 133

Response from Netscape Enterprise 4.1

$ nc netscape.example.com 80 GET / HTTP/3.0 HTTP/1.1 505 HTTP Version Not Supported Server: Netscape-Enterprise/4.1 Date: Mon, 16 Jun 2003 06:04: 04 GMT Content-length: 140 Content-type: text/HTML Connection: close

Response from a SunONE 6.1

$ nc sunone.example.com 80 GET / HTTP/3.0 HTTP/1.1 400 Bad request Server: Sun-ONE-Web-Server/6.1 Date: Tue, 16 Jan 2007 15:25:00 GMT Content-length: 0 Content-type: text/html Connection: close

We notice that every server answers in a different way. The answer also differs in the version of the server. Similar observations can be done we create requests with a non-existent protocol. Consider the following responses:

Response from Apache 1.3.23

$ nc apache.example.com 80 GET / JUNK/1.0 HTTP/1.1 200 OK Date: Sun, 15 Jun 2003 17:17: 47 GMT Server: Apache/1.3.23 Last-Modified: Thu, 27 Feb 2003 03:48: 19 GMT ETag: 32417-c4-3e5d8a83 Accept-Ranges: bytes Content-Length: 196 Connection: close Content-Type: text/HTML

Response from IIS 5.0

$ nc iis.example.com 80 GET / JUNK/1.0 HTTP/1.1 400 Bad Request Server: Microsoft-IIS/5.0 Date: Fri, 01 Jan 1999 20:14: 34 GMT Content-Type: text/HTML Content-Length: 87

Response from Netscape Enterprise 4.1

$ nc netscape.example.com 80 GET / JUNK/1.0 <HTML><HEAD><TITLE>Bad request</TITLE></HEAD> <BODY><H1>Bad request</H1> Your browser sent to query this server could not understand. </BODY></HTML>

Response from a SunONE 6.1

$ nc sunone.example.com 80 GET / JUNK/1.0 <HTML><HEAD><TITLE>Bad request</TITLE></HEAD> <BODY><H1>Bad request</H1> Your browser sent a query this server could not understand. </BODY></HTML>

Tools

- httprint - http://net-square.com/httprint.html

- httprecon - http://www.computec.ch/projekte/httprecon/

- Netcraft - http://www.netcraft.com

- Desenmascarame - http://desenmascara.me

Automated Testing

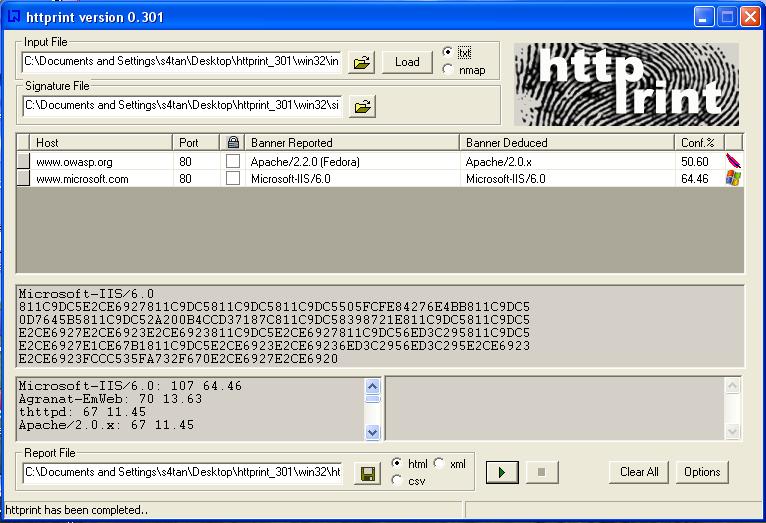

Rather than rely on manual banner grabbing and analysis of the web server headers, a tester can use automated tools to achieve the same results. The tests to carryout in order to accurately fingerprint a web server can be many. Luckily, there are tools that automate these tests. "httprint" is one of such tools. httprint uses a signature dictionary that allows it to recognize the type and the version of the web server in use.

An example of running httprint is shown below:

Online Testing

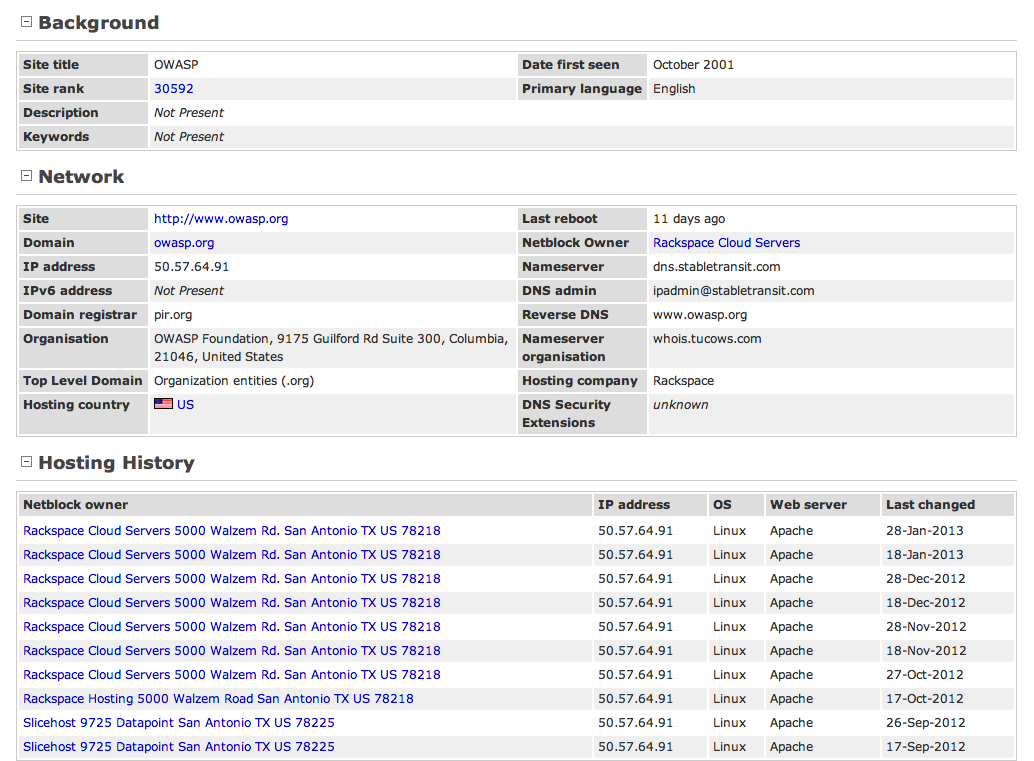

Online tools can be used if the tester wishes to test more stealthily and doesn't wish to directly connect to the target website. An example of an online tool that often delivers a lot of information about target Web Servers, is Netcraft. With this tool we can retrieve information about operating system, web server used, Server Uptime, Netblock Owner, history of change related to Web server and O.S.

An example is shown below:

OWASP Unmaskme Project is expected to become another online tool to do fingerprinting of any website with an overall interpretation of all the Web-metadata extracted. The idea behind this project is that anyone in charge of a website could test the metadata their site is showing to the world and assess it from a security point of view.

While this project is still being developed, you can test a Spanish Proof of Concept of this idea.

Vulnerability References

Whitepapers

- Saumil Shah: "An Introduction to HTTP fingerprinting" - http://www.net-square.com/httprint_paper.html

- Anant Shrivastava : "Web Application Finger Printing" - http://anantshri.info/articles/web_app_finger_printing.html

Remediation

Protect the presentation layer web server behind a hardened reverse proxy.

Obfuscate the presentation layer web server headers.

- Apache

- IIS