This site is the archived OWASP Foundation Wiki and is no longer accepting Account Requests.

To view the new OWASP Foundation website, please visit https://owasp.org

Testing for Brute Force (OWASP-AT-004)

OWASP Testing Guide v3 Table of Contents

This article is part of the OWASP Testing Guide v3. The entire OWASP Testing Guide v3 can be downloaded here.

OWASP at the moment is working at the OWASP Testing Guide v4: you can browse the Guide here

Brief Summary

Brute forcing consists of systematically enumerating all possible candidates for the solution and checking whether each candidate satisfies the problem's statement. In web application testing, the problem we are going to face with the most is very often connected with the need of having a valid user account to access the inner part of the application. Therefore we are going to check different types of authentication schema and the effectiveness of different brute-force attacks.

Related Security Activities

Description of Brute Force Vulnerabilities

See the OWASP article on Brute Force Attacks.

Description of the Issue

A great majority of web applications provide a way for users to authenticate themselves. By having knowledge of user's identity it's possible to create protected areas or, more generally, to have the application behave differently upon the logon of different users. In general, there are several methods for a user to authenticate to a system, like certificates, biometric devices, OTP (One Time Password) tokens. However, in web applications, we usually find a combination of user ID and password. Therefore, it's possible to carry out an attack to retrieve a valid user account and password, by trying to enumerate many (i.e., dictionary attack) or all the possible candidates.

After a successful brute force attack, a malicious user could have access to:

- Confidential information / data;

- Private sections of a web application could disclose confidential documents, users' profile data, financial status, bank details, users' relationships, etc.

- Administration panels;

- These sections are used by webmasters to manage (modify, delete, add) web application content, manage user provisioning, assign different privileges to the users, etc.

- Availability of further attack vectors;

- Private sections of a web application could hide dangerous vulnerabilities and contain advanced functionalities not available to public users.

Black Box testing and example

To leverage different brute forcing attacks, it's important to discover the type of authentication method used by the application, because the techniques and the tools to be used may change accordingly.

Discovery Authentication Methods

Unless an entity decides to apply a sophisticated web authentication, the two most commonly seen methods are as follows:

- HTTP Authentication;

- Basic Access Authentication

- Digest Access Authentication

- HTML Form-based Authentication;

The following sections provide some good information on identifying the authentication mechanism employed during a blackbox test.

HTTP authentication

There are two native HTTP access authentication schemes available to an organization – Basic and Digest.

- Basic Access Authentication

Basic Access Authentication assumes clients will identify themselves with a login name (e.g., "owasp") and password (e.g., "password"). When the client browser initially accesses a site using this scheme, the web server will reply with a 401 response containing a “WWW-Authenticate” header, containing a value of “Basic” and the name of the protected realm (e.g., WWW-Authenticate: Basic realm="wwwProtectedSite”). The client browser will then prompt the user for her login name and password for that realm. The client browser then responds to the web server with an “Authorization” header, containing the value “Basic” and the base64-encoded concatenation of the login name, a colon, and the password (e.g., Authorization: Basic b3dhc3A6cGFzc3dvcmQ=). Unfortunately, the authentication reply can be easily decoded should an attacker sniff the transmission.

Request and Response Test:

1. Client sends standard HTTP request for resource:

GET /members/docs/file.pdf HTTP/1.1 Host: target

2. The web server states that the requested resource is located in a protected directory.

3. Server sends response with HTTP 401 Authorization Required:

HTTP/1.1 401 Authorization Required Date: Sat, 04 Nov 2006 12:52:40 GMT WWW-Authenticate: Basic realm="User Realm" Content-Length: 401 Keep-Alive: timeout=15, max=100 Connection: Keep-Alive Content-Type: text/html; charset=iso-8859-1

4. Browser displays challenge pop-up for username and password data entry.

5. Client resubmits HTTP Request with credentials included:

GET /members/docs/file.pdf HTTP/1.1 Host: target Authorization: Basic b3dhc3A6cGFzc3dvcmQ=

6. Server compares client information to its credentials list.

7. If the credentials are valid, the server sends the requested content. If the authorization fails, the server resends HTTP status code 401. If the user clicks Cancel the browser will likely display an error message. If an attacker is able to intercept the request from step 5, the string

b3dhc3A6cGFzc3dvcmQ=

could simply be base64 decoded as follows (Base64 Decoded):

owasp:password

If the tester is able to intercept the HTTP request of a basic authentication request, it is not necessary to apply brute-force techniques to uncover the credentials. Simply use a base64 decoder on the sniffed request. However, if the tester is unable to intercept the HTTP request, the tester should use brute force tools.

- Digest Access Authentication

Digest Access Authentication expands upon the security of Basic Access Authentication by using a one-way cryptographic hashing algorithm (MD5) to encrypt authentication data and, secondly, adding a single use (connection unique) “nonce” value set by the web server. This value is used by the client browser in the calculation of a hashed password response. While the password is obscured by the use of the cryptographic hashing and the use of the nonce value precludes the threat of a replay attack, the login name is submitted in clear text.

Request and Response Test:

1. Here is an example of the initial Response header when handling an HTTP Digest target:

HTTP/1.1 401 Unauthorized

WWW-Authenticate: Digest realm="OwaspSample",

nonce="Ny8yLzIwMDIgMzoyNjoyNCBQTQ",

opaque="0000000000000000", \

stale=false,

algorithm=MD5,

qop="auth"

2. The Subsequent response headers with valid credentials would look like this:

GET /example/owasp/test.asmx HTTP/1.1

Accept: */*

Authorization: Digest username="owasp",

realm="OwaspSample",

qop="auth",

algorithm="MD5",

uri="/example/owasp/test.asmx",

nonce="Ny8yLzIwMDIgMzoyNjoyNCBQTQ",

nc=00000001,

cnonce="c51b5139556f939768f770dab8e5277a",

opaque="0000000000000000",

response="2275a9ca7b2dadf252afc79923cd3823"

HTML Form-based Authentication

While both HTTP access authentication schemes may appear suitable for commercial use over the Internet, particularly when used over an SSL encrypted session, many organizations have chosen to utilize custom HTML and application level authentication procedures, in order to provide a more sophisticated authentication procedure.

Source code taken from a HTML form:

<form method="POST" action="login"> <input type="text" name"username"> <input type="password" name="password"> </form>

Brute force Attacks

After having listed the different types of authentication methods for a web application, we will explain several types of brute force attacks.

- Dictionary Attack

Dictionary-based attacks consist of automated scripts and tools that will try to guess usernames and passwords from a dictionary file. A dictionary file can be tuned and compiled to cover words probably used by the owner of the account that a malicious user is going to attack. The attacker can gather information (via active/passive reconnaissance, competitive intelligence, dumpster diving, social engineering) to understand the user, or build a list of all unique words available on the website.

- Search Attacks

Search attacks will try to cover all possible combinations of a given character set and a given password length range. This kind of attack is very slow because the space of possible candidates is quite big. For example, given a known user ID, the total number of passwords to try, up to 8 characters in length, is equal to 26^(8) in a lower alpha charset (more than 200 billion possible passwords!).

- Rule-based search attacks

To increase the combination space coverage without slowing too much of the process, it's suggested to create good rules to generate candidates. For example, "John the Ripper" can generate password variations from part of the username or modify through a preconfigured mask words in the input (e.g., 1st round "pen" --> 2nd round "p3n" --> 3rd round "p3np3n").

Bruteforcing HTTP Basic Authentication

raven@blackbox /hydra $ ./hydra -L users.txt -P words.txt www.site.com http-head /private/ Hydra v5.3 (c) 2006 by van Hauser / THC - use allowed only for legal purposes. Hydra (http://www.thc.org) starting at 2009-07-04 18:15:17 [DATA] 16 tasks, 1 servers, 1638 login tries (l:2/p:819), ~102 tries per task [DATA] attacking service http-head on port 80 [STATUS] 792.00 tries/min, 792 tries in 00:01h, 846 todo in 00:02h [80][www] host: 10.0.0.1 login: owasp password: password [STATUS] attack finished for www.site.com (waiting for childs to finish) Hydra (http://www.thc.org) finished at 2009-07-04 18:16:34

Bruteforcing HTML Form Based Authentication

raven@blackbox /hydra $ ./hydra -L users.txt -P words.txt www.site.com https-post-form "/index.cgi:login&name=^USER^&password=^PASS^&login=Login:Not allowed" & Hydra v5.3 (c) 2006 by van Hauser / THC - use allowed only for legal purposes. Hydra (http://www.thc.org)starting at 2009-07-04 19:16:17 [DATA] 16 tasks, 1 servers, 1638 login tries (l:2/p:819), ~102 tries per task [DATA] attacking service http-post-form on port 443 [STATUS] attack finished for wiki.intranet (waiting for childs to finish) [443] host: 10.0.0.1 login: owasp password: password [STATUS] attack finished for www.site.com (waiting for childs to finish) Hydra (http://www.thc.org) finished at 2009-07-04 19:18:34

Gray Box testing and example

Partial knowledge of password and account details

When a tester has some information about length or password (account) structure, it's possible to perform a bruteforce attack with a higher probability of success. In fact, by limiting the number of characters and defining the password length, the total number of password values significantly decreases.

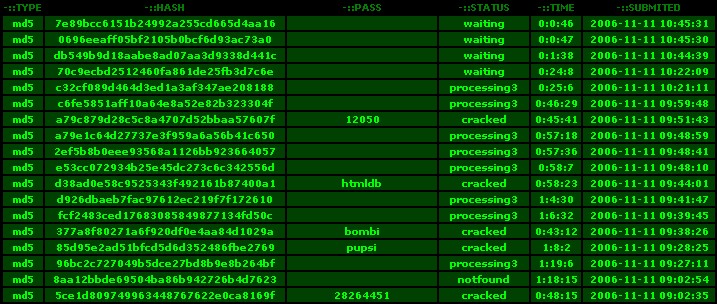

Memory Trade Off Attacks

To perform a Memory Trade Off Attack, the tester needs at least a password hash previously obtained by the tester by exploiting flaws in the application (e.g., SQL Injection) or sniffing HTTP traffic. Nowadays, the most common attacks of this kind are based on Rainbow Tables, a special type of lookup table used in recovering the plaintext password from a ciphertext generated by a one-way hash.

Rainbow tables are an optimization of Hellman's Memory Trade Off Attack, where the reduction algorithm is used to create chains with the purpose to compress the data output generated by computing all possible candidates.

Tables are specific to the hash function they were created for, e.g., MD5 tables can only crack MD5 hashes. The powerful RainbowCrack program was later developed that can generate and use rainbow tables for a variety of character sets and hashing algorithms, including LM hash, MD5, SHA1, etc.

References

Whitepapers

- Philippe Oechslin: Making a Faster Cryptanalytic Time-Memory Trade-Off - http://lasecwww.epfl.ch/pub/lasec/doc/Oech03.pdf

Links

- OPHCRACK (the time-memory-trade-off-cracker) - http://lasecwww.epfl.ch/~oechslin/projects/ophcrack/

- Project RainbowCrack - http://www.antsight.com/zsl/rainbowcrack/

- milw0rm - http://www.milw0rm.com/cracker/list.php

Tools

- THC Hydra: http://www.thc.org/thc-hydra/

- John the Ripper: http://www.openwall.com/john/

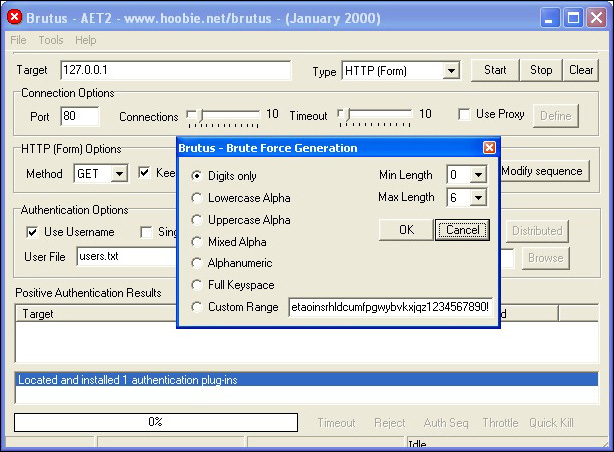

- Brutus http://www.hoobie.net/brutus/