This site is the archived OWASP Foundation Wiki and is no longer accepting Account Requests.

To view the new OWASP Foundation website, please visit https://owasp.org

Difference between revisions of "Category:Control"

m (Added external references) |

m (typo correction) |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

#Implement a Web Application Firewall (WAF) | #Implement a Web Application Firewall (WAF) | ||

#Error checking all input | #Error checking all input | ||

| − | #Use | + | #Use an automated scanner to look for security weaknesses |

#Output sanitization of error messages | #Output sanitization of error messages | ||

#Segregation development and production environments | #Segregation development and production environments | ||

Latest revision as of 01:13, 9 June 2015

This category is a parent category used to track categories of controls (or countermeasure, security mechanisms).

What is a control

As an abstract category of concepts, it can be difficult to grasp where controls fit into the collection of policies, procedures, and standards that create the structures of governance, management, practices and patterns necessary to secure software and data. Where each of these conceptual business needs is addressed through documentation with differing levels of specificity, it is useful to look at where controls fit in relation to these other structures. Security controls can be categorized in several ways. One useful breakdown is the axis that includes administrative, technical and physical controls. Controls in each of these areas support the others. Another useful breakdown is along the categories of preventive, detective and corrective.

ISACA defines control as the means of managing risk, including policies, procedures, guidelines, practices or organizational structures, which can be of an administrative, technical, management, or legal nature.[1]

While the ISACA COBIT standard is frequently referenced with regard to information security control, the design of the standard places its guidance mostly at the level of governance with very little that will help us design or implement secure software. U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication 800-53, Security and Privacy Controls for Federal Information Systems and Organizations is widely referenced for its fairly detailed catalog of security controls. It does not, however, define what a control should be.

The Council on CyberSecurity Critical Security Controls list provides very little detail on specific measures we can implement in software. Among the 20 critical controls we find "Application Software Security" with 11 recommended implementation measures:

- Patching

- Implement a Web Application Firewall (WAF)

- Error checking all input

- Use an automated scanner to look for security weaknesses

- Output sanitization of error messages

- Segregation development and production environments

- Secure code analysis, manual and automated

- Verify vendor security processes

- Database configuration hardening

- Train developers on writing secure code

- Remove development artifacts from production code

Of these 11, it is interesting to note that two relate to infrastructure architecture, four are operational, two are part of testing processes, and only three are things that are done as part of coding.

While many controls are definitely of a technical nature, it is important to distinguish the way in which controls differ from coding techniques. Many things we might think of as controls, should more properly be put into coding standards or guidelines. As an example, NIST SP800-53 suggests five controls related to session management:

- Concurrent Session Control

- Session Lock

- Session Termination

- Session Audit

- Session Authenticity

Note that three of these are included within the category of Access Controls. In most cases, NIST explicitly calls for the organization to define some of the elements of how these controls should be implemented.

In contrast, the OWASP Session_Management_Cheat_Sheet does a very good job at illustrating session management implementation techniques and suggests some standards. These kinds of standards and guidelines spell out specific implementation of controls.

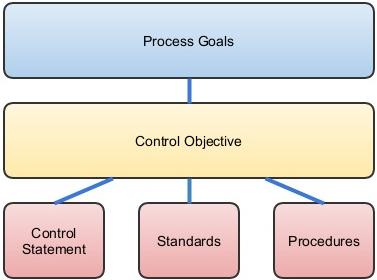

While different organizations and standards will write controls at differing levels of abstraction, it is generally recognized that controls should be defined and implemented to address business needs for security. COBIT 5 makes this explicit by mapping enterprise goals to IT-related goals, process goals, management practices and activities. The management practices map to items that were described in COBIT 4 as control objectives. Each organization and process area will define their controls differently, but this alignment of controls to objectives and activities is a strong commonality between different standards. Activities are often the means by which controls are implemented. They are written out in procedures that specify the intended operation of controls. A procedure is not, in itself, a control. A given procedure may address multiple controls and a given control may require more than one procedure to fully implement.

So, we've found that the concept of a security control is hard to define clearly in a way that enables practitioners to begin writing controls and putting them to use. Some definitions exist, but are open to wide interpretation and may not be adaptable to every need. At this point we can hazard some statements that may provide further clarity. Control statements should be concisely worded to specify required process outcomes. While this is very similar to a policy statement, policies are generally more oriented toward enterprise goals, whereas controls are more oriented toward process goals.

A control differs from a standard in that the standard is focused on requirements for specific tools that may be used, coding structures, or techniques.

Figure 1 - Relationship of control statements to control objectives and other documentation

Necessary controls in an application should be identified using risk assessment. Threat modeling is one component of risk assessment that examines the threats, vulnerabilities and exposures of an application. Threat modeling will help to identify many of the technical controls necessary for inclusion within the application development effort. It should be combined with other risk assessment techniques that also take into account the larger organizational impacts of the application.

Examples of controls

Further References

- Glossary. ISACA. http://www.isaca.org/Pages/Glossary.aspx?tid=2011&char=C As viewed on 24 May 2015.

- Cobit 5: Enabling Processes. ISACA. (2012). http://www.isaca.org/COBIT/Pages/COBIT-5-Enabling-Processes-product-page.aspx

- Joint Task Force Transformation Initiative. Security and Privacy Controls for Federal Information Systems and organizations. Special Publication 800-53 revision 4. (2013) U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology. http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.800-53r4

- Critical Security Controls. Center for Internet Security. Retrieved from http://www.cisecurity.org/critical-controls.cfm on 24 May 2015.

How to add a new Control article

You can follow the instructions to make a new Control article. Please use the appropriate structure and follow the Tutorial. Be sure to paste the following at the end of your article to make it show up in the Control category:

[[Category:Control]]

Subcategories

This category has the following 11 subcategories, out of 11 total.

A

C

E

I

L

S

Pages in category "Control"

The following 33 pages are in this category, out of 33 total.