This site is the archived OWASP Foundation Wiki and is no longer accepting Account Requests.

To view the new OWASP Foundation website, please visit https://owasp.org

Difference between revisions of "OWASP Mobile Security Project"

(→Guide Development Project) |

|||

| (67 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | = | + | =Main= |

| − | |||

| − | |||

{| style="padding: 0;margin:0;margin-top:10px;text-align:left;" |- | {| style="padding: 0;margin:0;margin-top:10px;text-align:left;" |- | ||

| − | | valign="top" | + | | valign="top" style="border-right: 1px dotted gray;padding-right:25px;" | |

== OWASP Mobile Security Project == | == OWASP Mobile Security Project == | ||

| Line 9: | Line 7: | ||

| + | == Maintenance notice == | ||

| + | |||

| + | This site is no longer maintained: please go to https://www2.owasp.org/www-project-mobile-security/ for our new website! | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The OWASP Mobile Security Project is a centralized resource intended to give developers and security teams the resources they need to build and maintain secure mobile applications. Through the project, our goal is to classify mobile security risks and provide developmental controls to reduce their impact or likelihood of exploitation. | ||

| + | The project is a breading ground for many different mobile security projects within OWASP. Right now, you can find the following active OWASP mobile security projects: | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | !Project/deliverable | ||

| + | !More info: | ||

| + | !Description: | ||

| + | !Current leaders | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Mobile Top Ten | ||

| + | |[https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Projects/OWASP_Mobile_Security_Project_-_Top_Ten_Mobile_Risks Project Page] | ||

| + | |The OWASP Mobile Security top 10 is created to raise awareness for the current mobile security issues. | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * [mailto:[email protected] Jason Haddix - HP Fortify] | ||

| + | * [mailto:[email protected] Daniel Miessler - HP Fortify] | ||

| + | * [mailto:[email protected] Jonathan Carter - Arxan Technologies] | ||

| + | *[mailto:[email protected] Milan Singh Thakur] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Mobile Security Testing Guide | ||

| + | |[[OWASP Mobile Security Testing Guide|Project Page]] | ||

| + | |A comprehensive manual for mobile app security testing and reverse engineering for iOS and Android mobile security testers as well as developers. | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * [mailto:[email protected] Sven Schleier] | ||

| + | * [mailto:[email protected] Jeroen Willemsen] | ||

| + | * [mailto:[email protected] Carlos Holguera] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Mobile Application Security Verification Standard | ||

| + | |[[OWASP Mobile Security Testing Guide|Project Page]] | ||

| + | |A standard for mobile app security which outlines the security requirements of a mobile application. | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * [mailto:[email protected] Sven Schleier] | ||

| + | * [mailto:[email protected] Jeroen Willemsen] | ||

| + | * [mailto:[email protected] Carlos Holguera] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Mobile Security Checklist | ||

| + | |[[OWASP Mobile Security Testing Guide|Project Page]] | ||

| + | |A checklist which allows easy mapping and scoring of the requirements from the Mobile Application Security Verification Standard based on the Mobile Security Testing Guide. | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * [mailto:[email protected] Sven Schleier] | ||

| + | * [mailto:[email protected] Jeroen Willemsen] | ||

| + | * [mailto:[email protected] Carlos Holguera] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |iGoat Tool Project | ||

| + | |[[OWASP iGoat Project|Project Page]] | ||

| + | |A learning tool for iOS developers (iPhone, iPad, etc.). It was inspired by the WebGoat project, and has a similar conceptual flow to it. | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * [mailto:[email protected] Swaroop Yermalkar] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Damn Vulnerable iOS Application | ||

| + | |[[OWASP DVIA|Project Page]] | ||

| + | |An iOS application that is damn vulnerable. Its main goal is to provide a platform to mobile security enthusiasts/professionals or students to test their iOS penetration testing skills in a legal environment. | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * [https://twitter.com/prateekg147 Prateek Gianchandani] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Android CK project | ||

| + | |[[Projects/OWASP Androick Project|Project Page]] | ||

| + | |A python tool to help in forensics analysis on android. | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * [https://twitter.com/phonesec Florian Pradines] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Seraphimdroid | ||

| + | |[[OWASP SeraphimDroid Project|Project Page]] | ||

| + | |A privacy and security protection app for Android devices. | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * [mailto:[email protected] Nikola Milosevic] | ||

| + | * [mailto:[email protected] Kartik Kholi] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Not what you are looking for? Please have a look at the '''[https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Mobile_Security_Project_Archive Mobile Security Page Archive]''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Want to start a new mobile security project? Follow https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Category:OWASP_Project#Starting_a_New_Project or contact one of the leaders of the active projects. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!-- DO NOT ALTER OR REMOVE THE TEXT ON NEXT LINE -->| valign="top" style="padding-left:25px;width:200px;border-right: 1px dotted gray;padding-right:25px;" | | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Active OWASP mobile projects == | ||

| + | * [[OWASP Mobile Security Testing Guide|OWASP Mobile Security Testing Guide]] | ||

| + | * [[OWASP Mobile Security Testing Guide|OWASP Mobile Application Security Verification Standard]] | ||

| + | * [[OWASP iGoat Tool Project]] | ||

| + | * [[OWASP DVIA|Damn Vulnerable iOS Application]] | ||

| + | * [[Projects/OWASP Androick Project|AndroidCK project]] | ||

| + | * [[OWASP SeraphimDroid Project|OWASP SeraphimDroid]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | = Top 10 Mobile Risks = | ||

| + | |||

| + | Please visit the [[OWASP Mobile Top 10|project page]] for current information. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == About this list == | ||

| + | In 2015, we performed a survey and initiated a Call for Data submission Globally . This helped us to analyze and re-categorize the OWASP Mobile Top Ten for 2016. So the top ten categories are now more focused on Mobile application rather than Server. | ||

| − | + | Our goals for the 2016 list included the following: | |

| − | + | * Updates to the wiki content; including cross-linking to testing guides, more visual exercises, etc; | |

| + | * Generation of more data; and | ||

| + | * A PDF release. | ||

| − | + | This list has been finalized after a 90-day feedback period from the community. Based on feedback, we have released a Mobile Top Ten 2016 list following a similar approach of collecting data, grouping the data in logical and consistent ways. | |

| − | + | Feel free to visit [https://groups.google.com/a/owasp.org/forum/#!forum/owasp-mobile-top-10-risks the mailing list] as well! | |

| − | + | == Top 10 Mobile Risks - Final List 2016 == | |

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2016-M1-Improper_Platform_Usage|M1: Improper Platform Usage]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2016-M2-Insecure_Data_Storage|M2: Insecure Data Storage]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2016-M3-Insecure_Communication|M3: Insecure Communication]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2016-M4-Insecure_Authentication|M4: Insecure Authentication]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2016-M5-Insufficient_Cryptography|M5: Insufficient Cryptography]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2016-M6-Insecure_Authorization|M6: Insecure Authorization]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2016-M7-Poor_Code_Quality|M7: Client Code Quality]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2016-M8-Code_Tampering|M8: Code Tampering]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2016-M9-Reverse_Engineering|M9: Reverse Engineering]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2016-M10-Extraneous_Functionality|M10: Extraneous Functionality]] | ||

| − | + | == Top 10 Mobile Risks - Final List 2014 == | |

| + | [[File:2014-01-26 20-23-29.png|right|550px]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2014-M1|M1: Weak Server Side Controls]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2014-M2|M2: Insecure Data Storage]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2014-M3|M3: Insufficient Transport Layer Protection]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2014-M4|M4: Unintended Data Leakage]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2014-M5|M5: Poor Authorization and Authentication]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2014-M6|M6: Broken Cryptography]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2014-M7|M7: Client Side Injection]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2014-M8|M8: Security Decisions Via Untrusted Inputs]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2014-M9|M9: Improper Session Handling]] | ||

| + | *[[Mobile_Top_10_2014-M10|M10: Lack of Binary Protections]] | ||

| − | + | == Project Methodology == | |

| − | '''We | + | * '''We adhered loosely to the [https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Top_10_2013/ProjectMethodology OWASP Web Top Ten Project methodology]. ''' |

| − | + | == Archive == | |

| + | * The list below is the OLD release candidate v1.0 of the OWASP Top 10 Mobile Risks. This list was initially released on September 23, 2011 at Appsec USA. | ||

| + | ** The original presentation can be found here: [http://www.slideshare.net/JackMannino/owasp-top-10-mobile-risks SLIDES]<br> | ||

| + | ** The corresponding video can be found here: [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GRvegLOrgs0 VIDEO] | ||

| + | ** [[Mobile_Top_10_2012|2011-12 Mobile Top Ten for archive purposes]] | ||

| − | + | = Mobile Security Testing Guide = | |

| − | + | Please see the [https://www.owasp.org/index.php/OWASP_Mobile_Security_Testing_Guide project page] for more details. | |

| − | + | =Acknowledgements = | |

| + | The OWASP Mobile Security project has a long history. It has been a source for many projects their predecessors as is clearly visible in [https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Mobile_Security_Project_Archive the archive]. | ||

== Project Leaders == | == Project Leaders == | ||

{{Template:Contact | {{Template:Contact | ||

| name = Jonathan Carter | | name = Jonathan Carter | ||

| email = [email protected] | | email = [email protected] | ||

| − | }}<br/> | + | }}<br /> |

{{Template:Contact | {{Template:Contact | ||

| name = Milan Singh Thakur | | name = Milan Singh Thakur | ||

| email = [email protected] | | email = [email protected] | ||

| username = Milan Singh Thakur | | username = Milan Singh Thakur | ||

| − | + | }}<br /> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | }}<br/> | ||

== Former Leaders == | == Former Leaders == | ||

{{Template:Contact | name = Mike Zusman | {{Template:Contact | name = Mike Zusman | ||

| email = [email protected] | | email = [email protected] | ||

| − | | username = schmoilito }}<br/> | + | | username = schmoilito }}<br /> |

{{Template:Contact | {{Template:Contact | ||

| name = Tony DeLaGrange | | name = Tony DeLaGrange | ||

| email = [email protected] | | email = [email protected] | ||

| username = Tony DeLaGrange | | username = Tony DeLaGrange | ||

| − | }}<br/> | + | }}<br /> |

{{Template:Contact | {{Template:Contact | ||

| name = Sarath Geethakumar | | name = Sarath Geethakumar | ||

| email = [email protected] | | email = [email protected] | ||

| username = Sarath Geethakumar | | username = Sarath Geethakumar | ||

| − | }}<br/> | + | }}<br /> |

{{Template:Contact | {{Template:Contact | ||

| name = Tom Eston | | name = Tom Eston | ||

| − | | email = teston@ | + | | email = teston@veracode.com |

| − | }}<br/> | + | | username = Tom Eston |

| + | }}<br /> | ||

{{Template:Contact | {{Template:Contact | ||

| name = Don Williams | | name = Don Williams | ||

| − | }}<br/> | + | }}<br /> |

{{Template:Contact | {{Template:Contact | ||

| name = Jason Haddix | | name = Jason Haddix | ||

| email = [email protected] | | email = [email protected] | ||

| username = Jason Haddix | | username = Jason Haddix | ||

| − | }}<br/> | + | }}<br /> |

== Top Contributors == | == Top Contributors == | ||

| Line 89: | Line 199: | ||

| email = [email protected] | | email = [email protected] | ||

| username = Zach_Lanier | | username = Zach_Lanier | ||

| − | }}<br/> | + | }}<br /> |

{{Template:Contact | {{Template:Contact | ||

| name = Ludovic Petit | | name = Ludovic Petit | ||

| email = [email protected] | | email = [email protected] | ||

| username = Ludovic Petit | | username = Ludovic Petit | ||

| − | }}<br/> | + | }}<br /> |

{{Template:Contact | {{Template:Contact | ||

| name = Swapnil Deshmukh | | name = Swapnil Deshmukh | ||

| email = [email protected] | | email = [email protected] | ||

| username = Swapnil Deshmukh | | username = Swapnil Deshmukh | ||

| − | }}<br/> | + | }}<br /> |

{{Template:Contact | {{Template:Contact | ||

| name = Beau Woods | | name = Beau Woods | ||

| email = [email protected] | | email = [email protected] | ||

| username = Beau Woods | | username = Beau Woods | ||

| − | }}<br/> | + | }}<br /> |

{{Template:Contact | {{Template:Contact | ||

| name = David Martin Aaron | | name = David Martin Aaron | ||

| email = [email protected] | | email = [email protected] | ||

| username = David Martin Aaron | | username = David Martin Aaron | ||

| − | }}<br/> | + | }}<br /> |

{{Template:Contact | {{Template:Contact | ||

| name = Luca De Fulgentis | | name = Luca De Fulgentis | ||

| email = [email protected] | | email = [email protected] | ||

| username = Daath | | username = Daath | ||

| − | }}<br/> | + | }}<br /> |

{{Template:Contact | {{Template:Contact | ||

| name = Andrew Pannell | | name = Andrew Pannell | ||

| email = [email protected] | | email = [email protected] | ||

| username = Andipannell | | username = Andipannell | ||

| − | }}<br/> | + | }}<br /> |

{{Template:Contact | {{Template:Contact | ||

| name = Stephanie V | | name = Stephanie V | ||

| email = [email protected] | | email = [email protected] | ||

| username = Stephanie V | | username = Stephanie V | ||

| − | }}<br/> | + | }}<br /> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

= Secure M-Development = | = Secure M-Development = | ||

| Line 294: | Line 240: | ||

The OWASP Secure Development Guidelines provides developers with the knowledge they need to build secure mobile applications. An extendable framework will be provided that includes the core security flaws found across nearly all mobile platforms. It will be a living reference where contributors can plug in newly exposed APIs for various platforms and provide good/bad code examples along with remediation guidance for those issues. | The OWASP Secure Development Guidelines provides developers with the knowledge they need to build secure mobile applications. An extendable framework will be provided that includes the core security flaws found across nearly all mobile platforms. It will be a living reference where contributors can plug in newly exposed APIs for various platforms and provide good/bad code examples along with remediation guidance for those issues. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Status note == | ||

| + | '''Note: Given that the MASVS/MSTG is becoming the leading framework in terms of requirements, we will archive this page and merge requirements with the MASVS, this process is currently taken care of by Abderrahmane AFTAHI (see [https://github.com/OWASP/owasp-masvs/issues/189 the github issue for more details]) and Rocco Gränitz (see [https://github.com/OWASP/owasp-masvs/issues/203 the github issue for more details])''' | ||

== Mobile Application Coding Guidelines == | == Mobile Application Coding Guidelines == | ||

| Line 433: | Line 382: | ||

==OWASP/ENISA Collaboration== | ==OWASP/ENISA Collaboration== | ||

| − | OWASP and the European Network and Information Security Agency (ENISA) collaborated to build a joint set of controls. ENISA has published the results of the collaborative effort as the "Smartphone Secure Development Guideline": | + | OWASP and the European Network and Information Security Agency (ENISA) collaborated to build a joint set of controls. ENISA has published the results of the collaborative effort as the "Smartphone Secure Development Guideline", which is published in 2011 at: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/smartphone-secure-development-guidelines/at_download/fullReport. In 2017, an update was published by ENISA at https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/smartphone-secure-development-guidelines-2016. |

[[File:OWASP_Mobile_Top_10_Controls.jpg|center|800px]] | [[File:OWASP_Mobile_Top_10_Controls.jpg|center|800px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == Status note == | ||

| + | '''Note: Given that the MASVS/MSTG is becoming the leading framework in terms of requirements, we will archive this page and merge requirements with the MASVS, this process is currently taken care of by Abderrahmane AFTAHI (see [https://github.com/OWASP/owasp-masvs/issues/189 the github issue for more details]) and Rocco Gränitz (see [https://github.com/OWASP/owasp-masvs/issues/203 the github issue for more details])''' | ||

==Contributors== | ==Contributors== | ||

| Line 604: | Line 557: | ||

**Device certificates can be used for stronger device authentication.' | **Device certificates can be used for stronger device authentication.' | ||

| − | ''References" | + | ''References"'' |

*1.ENISA. Top Ten Smartphone Risks . [Online] http://www.enisa.europa.eu/act/application-security/smartphone-security-1/top-ten-risks. | *1.ENISA. Top Ten Smartphone Risks . [Online] http://www.enisa.europa.eu/act/application-security/smartphone-security-1/top-ten-risks. | ||

*2. OWASP. Top 10 mobile risks. [Online] https://www.owasp.org/index.php/OWASP_Mobile_Security_Project#tab=Top_Ten_Mobile_Risks. | *2. OWASP. Top 10 mobile risks. [Online] https://www.owasp.org/index.php/OWASP_Mobile_Security_Project#tab=Top_Ten_Mobile_Risks. | ||

| Line 630: | Line 583: | ||

This is the first release (February 2013) of the Mobile Application Threat Model developed by the initial project team (listed at the end of this release). Development began mid-2011 and is being released in beta form for public comment and input. It is by no means complete and some sections will need more contributions, details and also real world case studies. It's the hope of the project team that others in the community can help contribute to this project to further enhance and improve this threat model. | This is the first release (February 2013) of the Mobile Application Threat Model developed by the initial project team (listed at the end of this release). Development began mid-2011 and is being released in beta form for public comment and input. It is by no means complete and some sections will need more contributions, details and also real world case studies. It's the hope of the project team that others in the community can help contribute to this project to further enhance and improve this threat model. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Maintenance note === | ||

| + | |||

| + | We are in the process of creating a new threatmodel. Want to join? Drop a line at [https://github.com/OWASP/OWASP-Mobile-Threatmodel our threatmodel git]. | ||

===Mobile Threat Model Introduction Statement=== | ===Mobile Threat Model Introduction Statement=== | ||

| Line 816: | Line 773: | ||

* '''App Store Approvers/Reviewers:''' Any app store which fails to review potentially dangerous code or malicious application which executes on a user’s device and performs suspicious/ malicious activities | * '''App Store Approvers/Reviewers:''' Any app store which fails to review potentially dangerous code or malicious application which executes on a user’s device and performs suspicious/ malicious activities | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| Line 825: | Line 780: | ||

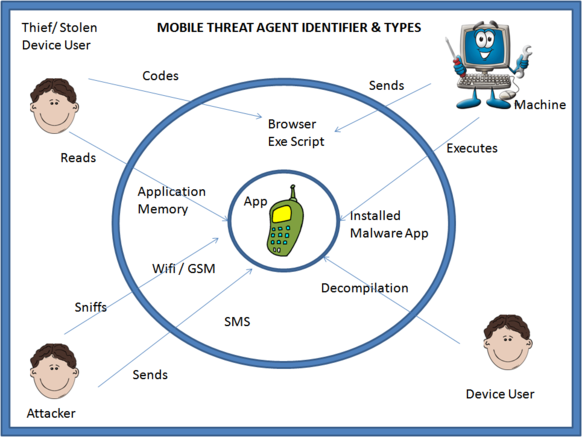

| − | * '''Malware on the device''': Any program / mobile application which performs suspicious activity. It can be an application, which is copying real time data from the user’s device and transmitting it to any server. This type of program executes parallel to all the processes running in the background and stays alive performing malicious activity all the time. E.g. Olympics App which stole text messages and browsing history:[http://venturebeat.com/2012/08/06/olympics-android-app/ | + | * '''Malware on the device''': Any program / mobile application which performs suspicious activity. It can be an application, which is copying real time data from the user’s device and transmitting it to any server. This type of program executes parallel to all the processes running in the background and stays alive performing malicious activity all the time. E.g. Olympics App which stole text messages and browsing history:[http://venturebeat.com/2012/08/06/olympics-android-app/]http://venturebeat.com/2012/08/06/olympics-android-app/ |

* '''Scripts executing at the browser with HTML5''': Any script code written in a language similar to JavaScript having capability of accessing the device level content falls under this type of agent section. A script executing at the browser reading and transmitting browser memory data / complete device level data. | * '''Scripts executing at the browser with HTML5''': Any script code written in a language similar to JavaScript having capability of accessing the device level content falls under this type of agent section. A script executing at the browser reading and transmitting browser memory data / complete device level data. | ||

| Line 993: | Line 948: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

__NOTOC__ <headertabs /> | __NOTOC__ <headertabs /> | ||

Latest revision as of 17:48, 22 October 2019

- Main

- Top 10 Mobile Risks

- Mobile Security Testing Guide

- Acknowledgements

- Secure M-Development

- Top 10 Mobile Controls

- M-Threat Model Project

OWASP Mobile Security Project

Maintenance noticeThis site is no longer maintained: please go to https://www2.owasp.org/www-project-mobile-security/ for our new website!

Not what you are looking for? Please have a look at the Mobile Security Page Archive Want to start a new mobile security project? Follow https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Category:OWASP_Project#Starting_a_New_Project or contact one of the leaders of the active projects. |

Active OWASP mobile projects |

Please visit the project page for current information.

About this list

In 2015, we performed a survey and initiated a Call for Data submission Globally . This helped us to analyze and re-categorize the OWASP Mobile Top Ten for 2016. So the top ten categories are now more focused on Mobile application rather than Server.

Our goals for the 2016 list included the following:

- Updates to the wiki content; including cross-linking to testing guides, more visual exercises, etc;

- Generation of more data; and

- A PDF release.

This list has been finalized after a 90-day feedback period from the community. Based on feedback, we have released a Mobile Top Ten 2016 list following a similar approach of collecting data, grouping the data in logical and consistent ways.

Feel free to visit the mailing list as well!

Top 10 Mobile Risks - Final List 2016

- M1: Improper Platform Usage

- M2: Insecure Data Storage

- M3: Insecure Communication

- M4: Insecure Authentication

- M5: Insufficient Cryptography

- M6: Insecure Authorization

- M7: Client Code Quality

- M8: Code Tampering

- M9: Reverse Engineering

- M10: Extraneous Functionality

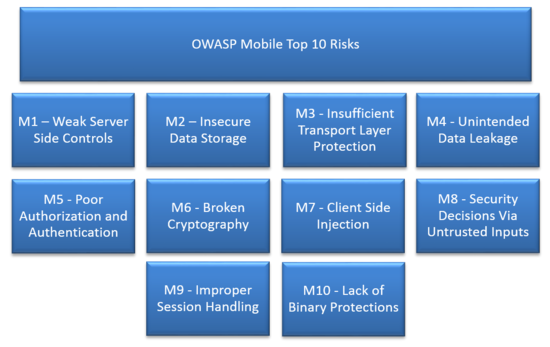

Top 10 Mobile Risks - Final List 2014

- M1: Weak Server Side Controls

- M2: Insecure Data Storage

- M3: Insufficient Transport Layer Protection

- M4: Unintended Data Leakage

- M5: Poor Authorization and Authentication

- M6: Broken Cryptography

- M7: Client Side Injection

- M8: Security Decisions Via Untrusted Inputs

- M9: Improper Session Handling

- M10: Lack of Binary Protections

Project Methodology

- We adhered loosely to the OWASP Web Top Ten Project methodology.

Archive

- The list below is the OLD release candidate v1.0 of the OWASP Top 10 Mobile Risks. This list was initially released on September 23, 2011 at Appsec USA.

- The original presentation can be found here: SLIDES

- The corresponding video can be found here: VIDEO

- 2011-12 Mobile Top Ten for archive purposes

- The original presentation can be found here: SLIDES

Please see the project page for more details.

The OWASP Mobile Security project has a long history. It has been a source for many projects their predecessors as is clearly visible in the archive.

Project Leaders

Jonathan Carter @

Milan Singh Thakur @

Former Leaders

Mike Zusman @

Tony DeLaGrange @

Sarath Geethakumar @

Tom Eston @

Don Williams

Jason Haddix @

Top Contributors

Zach Lanier @

Ludovic Petit @

Swapnil Deshmukh @

Beau Woods @

David Martin Aaron @

Luca De Fulgentis @

Andrew Pannell @

Stephanie V @

Secure Mobile Development Guidelines Objective

The OWASP Secure Development Guidelines provides developers with the knowledge they need to build secure mobile applications. An extendable framework will be provided that includes the core security flaws found across nearly all mobile platforms. It will be a living reference where contributors can plug in newly exposed APIs for various platforms and provide good/bad code examples along with remediation guidance for those issues.

Status note

Note: Given that the MASVS/MSTG is becoming the leading framework in terms of requirements, we will archive this page and merge requirements with the MASVS, this process is currently taken care of by Abderrahmane AFTAHI (see the github issue for more details) and Rocco Gränitz (see the github issue for more details)

Mobile Application Coding Guidelines

The purpose of this section is to provide application developers guidelines on how to build secure mobile applications, given the differences in security threat between applications running on a typical desktop as compared to those running on a mobile device (such as tablets or cell phones).

Using the guidance provided here, developers should code their applications to mitigate these malicious attacks. While more general coding guidelines should still be followed as applicable, this page lists additional considerations and/or modifications to common guidelines and is written using the best knowledge available at this time.

Authentication and Password Management

This is a set of controls used to verify the identity of a user, or other entity, interacting with the software, and also to ensure that applications handle the management of passwords in a secure fashion.

- Instances where the mobile application requires a user to create a password or PIN (say for offline access), the application should never use a PIN but enforce a password which follows a strong password policy.

- Mobile devices may offer the possibility of using password patterns which are never to be utilized in place of passwords as sufficient entropy cannot be ensured and they are easily vulnerable to smudge-attacks.

- Mobile devices may also offer the possibility of using biometric input to perform authentication which should never be used due to issues with false positives/negatives, among others.

- Wipe/clear memory locations holding passwords directly after their hashes are calculated.

- Based on risk assessment of the mobile application, consider utilizing two-factor authentication.

- For device authentication, avoid solely using any device-provided identifier (like UID or MAC address) to identify the device, but rather leverage identifiers specific to the application as well as the device (which ideally would not be reversible). For instance, create an app-unique “device-factor” during the application install or registration (such as a hashed value which is based off of a combination of the length of the application package file itself, as well as the current date/time, the version of the OS which is in use, and a randomly generated number). In this manner the device could be identified (as no two devices should ever generate the same “device-factor” based on these inputs) without revealing anything sensitive. This app-unique device-factor can be used with user authentication to create a session or used as part of an encryption key.

- In scenarios where offline access to data is needed, add an intentional X second delay to the password entry process after each unsuccessful entry attempt (2 is reasonable, also consider a value which doubles after each incorrect attempt).

- In scenarios where offline access to data is needed, perform an account/application lockout and/or application data wipe after X number of invalid password attempts (10 for example).

- When utilizing a hashing algorithm, use only a NIST approved standard such as SHA-2 or an algorithm/library.

- Salt passwords on the server-side, whenever possible. The length of the salt should at least be equal to, if not bigger than the length of the message digest value that the hashing algorithm will generate.

- Salts should be sufficiently random (usually requiring them to be stored) or may be generated by pulling constant and unique values off of the system (by using the MAC address of the host for example or a device-factor; see 3.1.2.g.). Highly randomized salts should be obtained via the use of a Cryptographically Secure Pseudorandom Number Generator (CSPRNG). When generating seed values for salt generation on mobile devices, ensure the use of fairly unpredictable values (for example, by using the x,y,z magnetometer and/or temperature values) and store the salt within space available to the application.

- Provide feedback to users on the strength of passwords during their creation.

- Based on a risk evaluation, consider adding context information (such as IP location, etc…) during authentication processes in order to perform Login Anomaly Detection.

- Instead of passwords, use industry standard authorization tokens (which expire as frequently as practicable) which can be securely stored on the device (as per the OAuth model) and which are time bounded to the specific service, as well as revocable (if possible server side).

- Integrate a CAPTCHA solution whenever doing so would improve functionality/security without inconveniencing the user experience too greatly (such as during new user registrations, posting of user comments, online polls, “contact us” email submission pages, etc…).

- Ensure that separate users utilize different salts.

Code Obfuscation

This is a set of controls used to prevent reverse engineering of the code, increasing the skill level and the time required to attack the application.

- Abstract sensitive software within static C libraries.

- Obfuscate all sensitive application code where feasible by running an automated code obfuscation program using either 3rd party commercial software or open source solutions.

- For applications containing sensitive data, implement anti-debugging techniques (e.g. prevent a debugger from attaching to the process; android:debuggable=”false”).

- Ensure logging is disabled as logs may be interrogated other applications with readlogs permissions (e.g. on Android system logs are readable by any other application prior to being rebooted).

- So long as the architecture(s) that the application is being developed for supports it (iOS 4.3 and above, Android 4.0 and above), Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) should be taken advantage of to hide executable code which could be used to remotely exploit the application and hinder the dumping of application’s memory.

Communication Security

This is a set of controls to help ensure the software handles the sending and receiving of information in a secure manner.

- Assume the provider network layer is insecure. Modern network layer attacks can decrypt provider network encryption, and there is no guarantee a Wi-Fi network (if in-use by the mobile device) will be appropriately encrypted.

- Ensure the application actually and properly validates (by checking the expiration date, issuer, subject, etc…) the server’s SSL certificate (instead of checking to see if a certificate is simply present and/or just checking if the hash of the certificate matches). To note, there are third party libraries to assist in this; search on “certificate pinning”.

- The application should only communicate with and accept data from authorized domain names/systems. It is permissible to allow application updates which will modify the list of authorized systems and/or for authorized systems to obtain a token from an authentication server, present a token to the client which the client will accept.

- To protect against attacks which utilize software such as SSLStrip, implement controls to detect if the connection is not HTTPS with every request when it is known that the connection should be HTTPS (e.g. use JavaScript, Strict Transport Security HTTP Header, disable all HTTP traffic).

- The UI should make it as easy as possible for the user to find out if a certificate is valid (so the user is not totally reliant upon the application properly validating any certificates).

- When using SSL/TLS, use certificates signed by trusted Certificate Authority (CA) providers.

Data Storage and Protection

This is a set of controls to help ensure the software handles the storing and handling of information in a secure manner. Given that mobile devices are mobile, they have a higher likelihood of being lost or stolen which should be taken into consideration here.

- Only collect and disclose data which is required for business use of the application. Identify in the design phase what data is needed, its sensitivity and whether it is appropriate to collect, store and use each data type.

- Classify data storage according to sensitivity and apply controls accordingly (e.g. passwords, personal data, location, error logs, etc.). Process, store and use data according to its classification

- Store sensitive data on the server instead of the client-end device, whenever possible. Assume any data written to device can be recovered.

- Beyond the time required by the application, don’t store sensitive information on the device (e.g. GPS/tracking).

- Do not store temp/cached data in a world readable directory. Assume shared storage is untrusted.

- Encrypt sensitive data when storing or caching it to non-volatile memory (using a NIST approved encryption standard such as AES-256, 3DES, or Skipjack).

- Use the PBKDF2 function to generate strong keys for encryption algorithms while ensuring high entropy as much as possible. The number of iterations should be set as high as may be tolerated for the environment (with a minimum of 1000 iterations) while maintaining acceptable performance.

- Sensitive data (such as encryption keys, passwords, credit card #’s, etc…) should stay in RAM for as little time as possible.

- Encryption keys should not remain in RAM during the instance lifecycle of the app. Instead, keys should be generated real time for encryption/decryption as needed and discarded each time.

- So long as the architecture(s) that the application is being developed for supports it (iOS 4.3 and above, Android 4.0 and above), Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) should be taken advantage of to limit the impact of attacks such as buffer overflows.

- Do not store sensitive data in the keychain of iOS devices due to vulnerabilities in their cryptographic mechanisms.

- Ensure that sensitive data (e.g. passwords, keys etc.) are not visible in cache or logs.

- Never store any passwords in clear text within the native application itself nor on the browser (e.g. save password feature on the browser).

- When displaying sensitive information (such as full account numbers), ensure that the sensitive information is cleared from memory (such as from the webView) when no longer needed/displayed.

- Do not store sensitive information in the form of typical strings. Instead use character arrays or NSMutableString (iOS specific) and clear their contents after they are no longer needed. This is because strings are typically immutable on mobile devices and reside within memory even when assigned (pointed to) a new value.

- Do not store sensitive data on external storage like SD cards if it can be avoided.

- Consider restricting access to sensitive data based on contextual information such as location (e.g. wallet app not usable if GPS data shows phone is outside Europe, car key not usable unless within 100m of car etc...).

- Use non-persistent identifiers which are not shared with other apps wherever possible - e.g. do not use the device ID number as an identifier, use a randomly generated number instead.

- Make use of remote wipe and kill switch APIs to remove sensitive information from the device in the event of theft or loss.

- Use a time based (expiry) type of control which will wipe sensitive data from the mobile device once the application has not communicated with its servers for a given period of time.

- Automatic application shutdown and/or lockout after X minutes of inactivity (e.g. 5 mins of inactivity).

- Avoid cached application snapshots in iOS: iOS can capture and store screen captures and store them as images when an application suspends. To avoid any sensitive data getting captured, use one or both of the following options: 1. Use the ‘willEnterBackground’ callback, to hide all the sensitive data. 2. Configure the application in the info.plist file to terminate the app when pushed to background (only use if multitasking is disabled).

- Prevent applications from being moved and/or run from external storage such as via SD cards.

- When handling sensitive data which does not need to be presented to users (e.g. account numbers), instead of using the actual value itself, use a token which maps to the actual value on the server-side. This will prevent exposure of sensitive information.

Paywall Controls

This is a set of practices to ensure the application properly enforces access controls related to resources which require payment in order to access (such as access to premium content, access to additional functionality, access to improved support, etc…).

- Maintain logs of access to paid-for resources in a non-repudiable format (e.g. a signed receipt sent to a trusted server backend – with user consent) and make them securely available to the end-user for monitoring.

- Warn users and obtain consent for any cost implications for application behavior.

- Secure account/pricing/billing/item information as it relates to users. If client has made any purchases via the application for instance, we should ensure that what they bought, the size of purchase, the quantity of the purchase, etc… should all be treated as sensitive information.

- Use a white-list model by default for paid-for resource addressing.

- Check for anomalous usage patterns in paid-for resource usage and trigger re- authentication. E.g. significant change in location occurs, user-language changes, etc...

Server Controls

This is a set of practices to ensure the server side program which interfaces with the mobile application is properly safeguarded. These controls would also apply in cases where the mobile application may be integrating with vended solutions hosted outside of the typical network.

- Ensure that the backend system(s) are running with a hardened configuration with the latest security patches applied to the OS, Web Server and other application components.

- Ensure adequate logs are retained on the backend in order to detect and respond to incidents and perform forensics (within the limits of data protection law).

- Employ rate limiting and throttling on a per-user/IP basis (if user identification is available) to reduce the risk from DoS type of attacks.

- Carry out a specific check of your code for any sensitive data unintentionally transferred between the mobile application and the back-end servers, and other external interfaces (e.g. is location or other information included transmissions?).

- Ensure the server rejects all unencrypted requests which it knows should always arrive encrypted.

Session Management

This is a set of controls to help ensure mobile applications handle sessions in a secure manner.

- Perform a check at the start of each activity/screen to see if the user is in a logged in state and if not, switch to the login state.

- When an application’s session is timed out, the application should discard and clear all memory associated with the user data, and any master keys used to decrypt the data.

- Session tokens should be revocable (particularly on the server side).

- Use lower timeout values to invalidate expired sessions (in contrast to the typical timeout values on traditional (non-mobile) applications).

Use of 3rd Party Libraries/Code

This is a set of practices to ensure the application integrates securely with code produced from outside parties.

- Vet the security/authenticity of any third party code/libraries used in your mobile application (e.g. making sure they come from a reliable source, will continue to be supported, contain no backdoors) and ensure that adequate internal approval is obtained to use the code/library.

- Track all third party frameworks/API’s used in the mobile application for security patches and perform upgrades as they are released.

- Pay particular attention to validating all data received from and sent to non-trusted third party apps (e.g. ad network software) before incorporating their use into an application.

Mobile Application Provisioning/Distribution/Testing

This is a set of controls to ensure that software is tested and released relatively free of vulnerabilities, that there are mechanisms to report new security issues if they are found, and also that the software has been designed to accept patches in order to address potential security issues.

- Design & distribute applications to allow updates for security patches.

- Provide & advertise feedback channels for users to report security problems with applications (such as a [email protected] email address).

- Ensure that older versions of applications which contain security issues and are no longer supported are removed from app-stores/app-repositories.

- Periodically test all backend services (Web Services/REST) which interact with a mobile application as well as the application itself for vulnerabilities using enterprise approved automatic or manual testing tools (including internal code reviews).

- Based on risk assessment of the application, have the application go through Security Assessment for a review of security vulnerabilities following the Team’s internal security testing of the application.

- Utilize the Enterprise provisioning process (e.g. IDM) to request and approve access for users on the mobile application.

- Ensure the application is sufficiently obfuscated prior to release by conducting tests which attempt to reverse engineer the obfuscated application.

- Distribute applications via an app-store type of interface (when appropriate) as many app-stores monitor applications for insecure code which we may benefit from.

- Digitally sign applications using a code signing certificate obtained via a trusted Certificate Authority (CA).

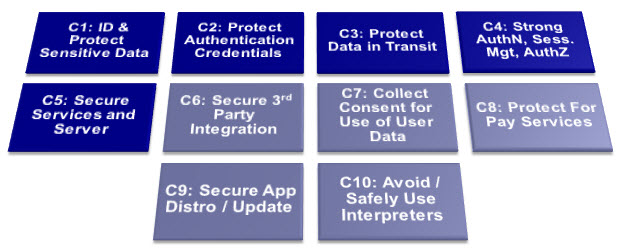

OWASP/ENISA Collaboration

OWASP and the European Network and Information Security Agency (ENISA) collaborated to build a joint set of controls. ENISA has published the results of the collaborative effort as the "Smartphone Secure Development Guideline", which is published in 2011 at: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/smartphone-secure-development-guidelines/at_download/fullReport. In 2017, an update was published by ENISA at https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/smartphone-secure-development-guidelines-2016.

Status note

Note: Given that the MASVS/MSTG is becoming the leading framework in terms of requirements, we will archive this page and merge requirements with the MASVS, this process is currently taken care of by Abderrahmane AFTAHI (see the github issue for more details) and Rocco Gränitz (see the github issue for more details)

Contributors

This document has been jointly produced with ENISA as well as the following individuals:

- Vinay Bansal, Cisco Systems

- Nader Henein, Research in Motion

- Giles Hogben, ENISA

- Karsten Nohl, Srlabs

- Jack Mannino, nVisium Security

- Christian Papathanasiou, Royal Bank of Scotland

- Stefan Rueping, Infineon

- Beau Woods, Stratigos Security

Top 10 mobile controls and design principles

1. Identify and protect sensitive data on the mobile device

Risks: Unsafe sensitive data storage, attacks on decommissioned phones unintentional disclosure: Mobile devices (being mobile) have a higher risk of loss or theft. Adequate protection should be built in to minimize the loss of sensitive data on the device.

- 1.1 In the design phase, classify data storage according to sensitivity and apply controls accordingly (e.g. passwords, personal data, location, error logs, etc.). Process, store and use data according to its classification. Validate the security of API calls applied to sensitive data.

- 1.2 Store sensitive data on the server instead of the client-end device. This is based on the assumption that secure network connectivity is sufficiently available and that protection mechanisms available to server side storage are superior. The relative security of client vs server-side security also needs to be assessed on a case-by-case basis (see ENISA cloud risk assessment (3) or the OWASP Cloud top 10 (4) for decision support).

- 1.3 When storing data on the device, use a file encryption API provided by the OS or other trusted source. Some platforms provide file encryption APIs which use a secret key protected by the device unlock code and deleteable on remote kill. If this is available, it should be used as it increases the security of the encryption without creating extra burden on the end-user. It also makes stored data safer in the case of loss or theft. However, it should be born in mind that even when protected by the device unlock key, if data is stored on the device, its security is dependent on the security of the device unlock code if remote deletion of the key is for any reason not possible.

- 1.4 Do not store/cache sensitive data (including keys) unless they are encrypted and if possible stored in a tamper-proof area (see control 2).

- 1.5 Consider restricting access to sensitive data based on contextual information such as location (e.g. wallet app not usable if GPS data shows phone is outside Europe, car key not usable unless within 100m of car etc...).

- 1.6 Do not store historical GPS/tracking or other sensitive information on the device beyond the period required by the application (see controls 1.7, 1.8).

- 1.7 Assume that shared storage is untrusted - information may easily leak in unexpected ways through any shared storage. In particular:

- Be aware of caches and temporary storage as a possible leakage channel, when shared with other apps.

- Be aware of public shared storage such as address book, media gallery and audio files as a possible leakage channel. For example storing images with location metadata in the media-gallery allows that information to be shared in unintended ways.

- Do not store temp/cached data in a world readable directory.

- 1.8 For sensitive personal data, deletion should be scheduled according to a maximum retention period, (to prevent e.g. data remaining in caches indefinitely).

- 1.9 There is currently no standard secure deletion procedure for flash memory (unless wiping the entire medium/card). Therefore data encryption and secure key management are especially important.

- 1.10 Consider the security of the whole data lifecycle in writing your application (collection over the wire, temporary storage, caching, backup, deletion etc)

- 1.11 Apply the principle of minimal disclosure - only collect and disclose data which is required for business use of the application. Identify in the design phase what data is needed, its sensitivity and whether it is appropriate to collect, store and use each data type.

- 1.12 Use non-persistent identifiers which are not shared with other apps wherever possible - e.g. do not use the device ID number as an identifier unless there is a good reason to do so (use a randomly generated number – see 4.3). Apply the same data minimization principles to app sessions as to http sessions/cookies etc.

- 1.13 Applications on managed devices should make use of remote wipe and kill switch APIs to remove sensitive information from the device in the event of theft or loss. (A kill-switch is the term used for an OS-level or purpose-built means of remotely removing applications and/or data).

- 1.14 Application developers may want to incorporate an application-specific "data kill switch" into their products, to allow the per-app deletion of their application's sensitive data when needed (strong authentication is required to protect misuse of such a feature).

2. Handle password credentials securely on the device

Risks: Spyware, surveillance, financial malware. A user's credentials, if stolen, not only provide unauthorized access to the mobile backend service, they also potentially compromise many other services and accounts used by the user. The risk is increased by the widespread of reuse of passwords across different services.

- 2.1 Instead of passwords consider using longer term authorization tokens that can be securely stored on the device (as per the OAuth model). Encrypt the tokens in transit (using SSL/TLS). Tokens can be issued by the backend service after verifying

Smartphones secure development guidelines for app developers the user credentials initially. The tokens should be time bounded to the specific service as well as revocable (if possible server side), thereby minimizing the damage in loss scenarios. Use the latest versions of the authorization standards (such as OAuth 2.0). Make sure that these tokens expire as frequently as practicable.

- 2.2 In case passwords need to be stored on the device, leverage the encryption and key-store mechanisms provided by the mobile OS to securely store passwords, password equivalents and authorization tokens. Never store passwords in clear text. Do not store passwords or long term session IDs without appropriate hashing or encryption.

- 2.3 Some devices and add-ons allow developers to use a Secure Element e.g. (5) (6) – sometimes via an SD card module - the number of devices offering this functionality is likely to increase. Developers should make use of such capabilities to store keys, credentials and other sensitive data. The use of such secure elements gives a higher level of assurance with the standard encrypted SD card certified at FIPS 140-2 Level 3. Using the SD cards as a second factor of authentication though possible, isn't recommended, however, as it becomes a pseudo-inseparable part of the device once inserted and secured.

- 2.4 Provide the ability for the mobile user to change passwords on the device.

- 2.5 Passwords and credentials should only be included as part of regular backups in encrypted or hashed form.

- 2.6 Smartphones offer the possibility of using visual passwords which allow users to memorize passwords with higher entropy. These should only be used however, if sufficient entropy can be ensured. (7)

- 2.7 Swipe-based visual passwords are vulnerable to smudge-attacks (using grease deposits on the touch screen to guess the password). Measures such as allowing repeated patterns should be introduced to foil smudge-attacks. (8)

- 2.8 Check the entropy of all passwords, including visual ones (see 4.1 below).

- 2.9 Ensure passwords and keys are not visible in cache or logs.

- 2.10 Do not store any passwords or secrets in the application binary. Do not use a generic shared secret for integration with the backend (like password embedded in code). Mobile application binaries can be easily downloaded and reverse engineered.

3. Ensure sensitive data is protected in transit

Risks: Network spoofing attacks, surveillance. The majority of smartphones are capable of using multiple network mechanisms including Wi-Fi, provider network (3G, GSM, CDMA and others), Bluetooth etc. Sensitive data passing through insecure channels could be intercepted. (9) (10)

- 3.1 Assume that the provider network layer is not secure. Modern network layer attacks can decrypt provider network encryption, and there is no guarantee that the Wi-Fi network will be appropriately encrypted.

- 3.2 Applications should enforce the use of an end-to-end secure channel (such as SSL/TLS) when sending sensitive information over the wire/air (e.g. using Strict Transport Security - STS (11)).This includes passing user credentials, or other authentication equivalents. This provides confidentiality and integrity protection.

- 3.3 Use strong and well-known encryption algorithms (e.g. AES) and appropriate key lengths (check current recommendations for the algorithm you use e.g. (12) page 53).

- 3.4 Use certificates signed by trusted CA providers. Be very cautious in allowing self- signed certificates. Do not disable or ignore SSL chain validation.

- 3.5 For sensitive data, to reduce the risk of man-in-middle attacks (like SSL proxy, SSL strip), a secure connection should only be established after verifying the identity of the remote end-point (server). This can be achieved by ensuring that SSL is only established with end-points having the trusted certificates in the key chain.

- 3.6 The user interface should make it as easy as possible for the user to find out if a certificate is valid.

- 3.7 SMS, MMS or notifications should not be used to send sensitive data to or from mobile end-points.

Reference: Google vulnerability of Client Login account credentials on unprotected wifi - [1]

4. Implement user authentication,authorization and session management correctly

Risks: Unauthorized individuals may obtain access to sensitive data or systems by circumventing authentication systems (logins) or by reusing valid tokens or cookies. (13)

- 4.1 Require appropriate strength user authentication to the application. It may be useful to provide feedback on the strength of the password when it is being entered for the first time. The strength of the authentication mechanism used depends on the sensitivity of the data being processed by the application and its access to valuable resources (e.g. costing money).

- 4.2 It is important to ensure that the session management is handled correctly after the initial authentication, using appropriate secure protocols. For example, require authentication credentials or tokens to be passed with any subsequent request (especially those granting privileged access or modification).

- 4.3 Use unpredictable session identifiers with high entropy. Note that random number generators generally produce random but predictable output for a given seed (i.e. the same sequence of random numbers is produced for each seed). Therefore it is important to provide an unpredictable seed for the random number generator. The standard method of using the date and time is not secure. It can be improved, for example using a combination of the date and time, the phone temperature sensor and the current x,y and z magnetic fields. In using and combining these values, well-tested algorithms which maximise entropy should be chosen (e.g. repeated application of SHA1 may be used to combine random variables while maintaining maximum entropy – assuming a constant maximum seed length).

- 4.4 Use context to add security to authentication - e.g. IP location, etc...

- 4.5 Where possible, consider using additional authentication factors for applications giving access to sensitive data or interfaces where possible - e.g. voice, fingerprint (if available), who-you-know, behavioural etc.

- 4.6 Use authentication that ties back to the end user identity (rather than the device identity).

5. Keep the backend APIs (services) and the platform (server) secure

Risks: Attacks on backend systems and loss of data via cloud storage. The majority of mobile applications interact with the backend APIs using REST/Web Services or proprietary protocols. Insecure implementation of backend APIs or services, and not keeping the back-end platform hardened/patched will allow attackers to compromise data on the mobile device when transferred to the backend, or to attack the backend through the mobile application. (14)

- 5.1 Carry out a specific check of your code for sensitive data unintentionally transferred, any data transferred between the mobile device and web-server back- ends and other external interfaces - (e.g. is location or other information included within file metadata).

- 5.2 All backend services (Web Services/REST) for mobile apps should be tested for vulnerabilities periodically, e.g. using static code analyser tools and fuzzing tools for testing and finding security flaws.

- 5.3 Ensure that the backend platform (server) is running with a hardened configuration with the latest security patches applied to the OS, Web Server and other application components.

- 5.4 Ensure adequate logs are retained on the backend in order to detect and respond to incidents and perform forensics (within the limits of data protection law).

- 5.5 Employ rate limiting and throttling on a per-user/IP basis (if user identification is available) to reduce the risk from DDoS attack.

- 5.6 Test for DoS vulnerabilities where the server may become overwhelmed by certain resource intensive application calls.

- 5.7 Web Services, REST and APIs can have similar vulnerabilities to web applications:

- Perform abuse case testing, in addition to use case testing

- Perform testing of the backend Web Service, REST or API to determine vulnerabilities.

6. Secure data integration with third party services and applications

Risks: Data leakage. Users may install applications that may be malicious and can transmit personal data (or other sensitive stored data) for malicious purposes.

- 6.1 Vet the security/authenticity of any third party code/libraries used in your mobile application (e.g. making sure they come from a reliable source, with maintenance supported, no backend Trojans)

- 6.2 Track all third party frameworks/APIs used in the mobile application for security patches. A corresponding security update must be done for the mobile applications using these third party APIs/frameworks.

- 6.3 Pay particular attention to validating all data received from and sent to non-trusted third party apps (e.g. ad network software) before processing within the application.

7. Pay specific attention to the collection and storage of consent for the collection and use of the user’s data

Risks: Unintentional disclosure of personal or private information, illegal data processing. In the European Union, it is mandatory to obtain user consent for the collection of personally identifiable information (PII). (15) (16)

- 7.1 Create a privacy policy covering the usage of personal data and make it available to the user especially when making consent choices.

- 7.2 Consent may be collected in three main ways:

- At install time

- At run-time when data is sent

- Via “opt-out” mechanisms where a default setting is implemented and the user has to turn it off.

- 7.3 Check whether your application is collecting PII - it may not always be obvious - for example do you use persistent unique identifiers linked to central data stores containing personal information?

- 7.4 Audit communication mechanisms to check for unintended leaks (e.g. image metadata).

- 7.5 Keep a record of consent to the transfer of PII. This record should be available to the user (consider also the value of keeping server-side records attached to any user data stored). Such records themselves should minimise the amount of personal data they store (e.g. using hashing).

- 7.6 Check whether your consent collection mechanism overlaps or conflicts (e.g. in the data handling practices stated) with any other consent collection within the same stack (e.g. APP-native + webkit HTML) and resolve any conflicts.

8. Implement controls to prevent unauthorized access to paid-for resources (wallet, SMS, phone calls etc.) Risks: Smartphone apps give programmatic (automatic) access to premium rate phone calls, SMS, roaming data, NFC payments, etc. Apps with privileged access to such API’s should take particular care to prevent abuse, considering the financial impact of vulnerabilities that giveattackers access to the user’s financial resources.

- 8.1 Maintain logs of access to paid-for resources in a non-repudiable format (e.g. a signed receipt sent to a trusted server backend – with user consent) and make them available to the end-user for monitoring. Logs should be protected from unauthorised access.

- 8.2 Check for anomalous usage patterns in paid-for resource usage and trigger re- authentication. E.g. when significant change in location occurs, user-language changes etc.

- 8.3 Consider using a white-list model by default for paid-for resource addressing - e.g. address book only unless specifically authorised for phone calls.

- 8.4 Authenticate all API calls to paid-for resources (e.g. using an app developer certificate).

- 8.5 Ensure that wallet API callbacks do not pass cleartext account/pricing/ billing/item information.

- 8.6 Warn user and obtain consent for any cost implications for app behaviour.

- 8.7 Implement best practices such as fast dormancy (a 3GPP specification), caching, etc. to minimize signalling load on base stations.

9. Ensure secure distribution/provisioning of mobile applications

Risks: Use of secure distribution practices is important in mitigating all risks described in the OWASP Mobile Top 10 Risks and ENISA top 10 risks.

- 9.1 Applications must be designed and provisioned to allow updates for security patches, taking into account the requirements for approval by app-stores and the extra delay this may imply.

- 9.2 Most app-stores monitor apps for insecure code and are able to remotely remove apps at short notice in case of an incident. Distributing apps through official app- stores therefore provides a safety-net in case of serious vulnerabilities in your app.

- 9.3Provide feedback channels for users to report security problems with apps – e.g. a security@ email address.

10. Carefully check any runtime interpretation of code for errors

Risks: Runtime interpretation of code may give an opportunity for untrusted parties to provide unverified input which is interpreted as code. For example, extra levels in a game, scripts, interpreted SMS headers. This gives an opportunity for malware to circumvent walled garden controls provided by app-stores. It can lead to injection attacks leading to Data leakage, surveillance, spyware, and diallerware.

Note that it is not always obvious that your code contains an interpreter. Look for any capabilities accessible via user-input data and use of third party API’s which may interpret user-input - e.g. JavaScript interpreters.

- 10.1 Minimize runtime interpretation and capabilities offered to runtime interpreters: run interpreters at minimal privilege levels.

- 10.2 Define comprehensive escape syntax as appropriate.

- 10.3 Fuzz test interpreters.

- 10.4 Sandbox interpreters.

Appendix A- Relevant General Coding Best Practices'

Some general coding best practices are particularly relevant to mobile coding. We have listed some of the most important tips here:

- Perform abuse case testing, in addition to use case testing.

- Validate all input.

- Minimise lines and complexity of code. A useful metric is cyclomatic complexity (17).

- Use safe languages (e.g. from buffer-overflow).

- Implement a security report handling point (address) [email protected]

- Use static and binary code analysers and fuzz-testers to find security flaws.

- Use safe string functions, avoid buffer and integer overflow.

- Run apps with the minimum privilege required for the application on the operating

system. Be aware of privileges granted by default by APIs and disable them.

- Don't authorize code/app to execute with root/system administrator privilege

- Always perform testing as a standard as well as a privileged user

- Avoid opening application-specific server sockets (listener ports) on the client device.

Use the communication mechanisms provided by the OS.

- Remove all test code before releasing the application

- Ensure logging is done appropriately but do not record excessive logs, especially those

including sensitive user information.

Appendix B- Enterprise Guidelines

- If a business-sensitive application needs to be provisioned on a device, applications should enforce of a higher security posture on the device (such as PIN, remote management/wipe, app monitoring)

- Device certificates can be used for stronger device authentication.'

References"

- 1.ENISA. Top Ten Smartphone Risks . [Online] http://www.enisa.europa.eu/act/application-security/smartphone-security-1/top-ten-risks.

- 2. OWASP. Top 10 mobile risks. [Online] https://www.owasp.org/index.php/OWASP_Mobile_Security_Project#tab=Top_Ten_Mobile_Risks.

- 3. Cloud Computing: Benefits, Risks and Recommendations for information security. [Online] 2009. http://www.enisa.europa.eu/act/rm/files/deliverables/cloud-computing-risk-assessment.

- 4. OWASP Cloud Top 10. [Online] https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Category:OWASP_Cloud_%E2%80%90_10_Project.

- 5. Blackberry developers documents. [Online] http://www.blackberry.com/developers/docs/7.0.0api/net/rim/device/api/io/nfc/se/SecureElement.h tml,.

- 6. Google Seek For Android. [Online] http://code.google.com/p/seek-for-android/.

- 7. Visualizing Keyboard Pattern Passwords. [Online] cs.wheatoncollege.edu/~mgousie/comp401/amos.pdf.

- 8. Smudge Attacks on Smartphone Touch Screens. Adam J. Aviv, Katherine Gibson, Evan Mossop, Matt Blaze, and Jonathan M. Smith. s.l. : Department of Computer and Information Science – University of Pennsylvania.

- 9. Google vulnerability of Client Login account credentials on unprotected . [Online] http://www.uni- ulm.de/in/mi/mitarbeiter/koenings/catching-authtokens.html.

- 10. SSLSNIFF. [Online] http://blog.thoughtcrime.org/sslsniff-anniversary-edition. 11. [Online] http://tools.ietf.org/html/draft-ietf-websec-strict-transport-sec-02.

Smartphones secure development guidelines for app developers

*12. NIST Computer Security. [Online] http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-57/sp800- 57_PART3_key-management_Dec2009.pdf.

- 13. Google's ClientLogin implementation . [Online] http://www.uni- ulm.de/in/mi/mitarbeiter/koenings/catching-authtokens.html.

- 14. [Online] https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Web_Services.

- 15. EU Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC. [Online] http://eur- lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31995L0046:en:HTML.

- 16. [Online] http://democrats.energycommerce.house.gov/sites/default/files/image_uploads/Testimony_05.04.11 _Spafford.pdf.

- 17. [Online] http://www.aivosto.com/project/help/pm-complexity.html.

- 18. [Online] http://code.google.com/apis/accounts/docs/AuthForInstalledApps.html.

- 19. Google Wallet Security. [Online] http://www.google.com/wallet/how-it-works-security.htm.

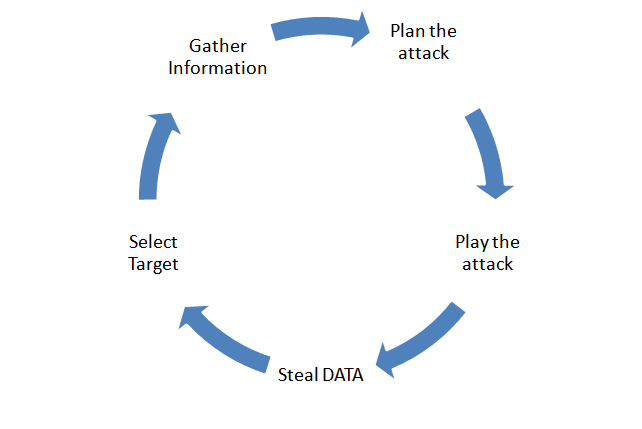

Mobile Application Threat Model - Beta Release

This is the first release (February 2013) of the Mobile Application Threat Model developed by the initial project team (listed at the end of this release). Development began mid-2011 and is being released in beta form for public comment and input. It is by no means complete and some sections will need more contributions, details and also real world case studies. It's the hope of the project team that others in the community can help contribute to this project to further enhance and improve this threat model.

Maintenance note

We are in the process of creating a new threatmodel. Want to join? Drop a line at our threatmodel git.

Mobile Threat Model Introduction Statement

Threat modeling is a systematic process that begins with a clear understanding of the system. It is necessary to define the following areas to understand possible threats to the application:

- Mobile Application Architecture - This area describes how the application is designed from device specific features used by the application, wireless transmission protocols, data transmission mediums, interaction with hardware components and other applications.

- Mobile Data - What data does the application store and process? What is the business purpose of this data and what are the data workflows?

- Threat Agent Identification - What are the threats to the mobile application and who are the threat agents. This area also outlines the process for defining what threats apply to the mobile application.

- Methods of Attack - What are the most common attacks utilized by threat agents. This area defines these attacks so that controls can be developed to mitigate attacks.

- Controls - What are the controls to prevent attacks. This is the last area to be defined only after previous areas have been completed by the development team.

Target Audience for the Mobile Threat Model

This model is to be used by mobile application developers and software architects as part of the “threat modeling” phase of a typical SDLC process. The model can also be used by Information Security Professionals that need to determine what typical mobile application threats are and provide a methodology for conducting basic threat modeling.

How to Use the Mobile Threat Model

This threat model is designed as an outline or checklist of items that need to be documented, reviewed and discussed when developing a mobile application. Every organization that develops mobile applications will have different requirements as well as threats. This model was designed to be as organizational and industry agnostic as possible so that any mobile application development team can use this as a guide for conducting threat modeling for their specific application. Real world case studies as examples will be integrated to this threat model in the near future.

Mobile Application Architecture

The mobile application architecture should, at the very least, describe device specific features used by the application, wireless transmission protocols, data transmission medium, interaction with hardware components and other applications. Applications can be mapped to this architecture as a preliminary attack surface assessment.

Architecture Considerations

Although mobile applications vary in function, they can be described using a generalized model as follows:

Wireless interfaces

Transmission Type

Hardware Interaction

Interaction with on device applications/services

Interaction with off device applications/services

Encryption Protocols

- What is the design of the architecture (network infrastructure, web services, trust boundaries, third-party APIs, etc)

- Carrier

- Data

- SMS

- Voice

- Endpoints

- Web Services

- RESTful or SOAP based

- Third Party (Example: Amazon)

- Websites

- Does the app utilize or integrate the “mobile web” version of an existing web site?

- App Stores

- Google Play

- Apple App Store

- Windows Mobile

- BlackBerry App Store

- Cloud Storage

- Amazon/Azure

- Corporate Networks (via VPN, ssh, etc.)

- Web Services

- Wireless interfaces

- 802.11

- NFC

- Bluetooth

- RFID

- Device

- App Layer

- Runtime Environment (VM, framework dependencies, etc)

- OS Platform

- Apple iOS

- Android

- Windows Mobile

- BlackBerry

- Baseband

- Carrier

- Common hardware components

- GPS

- Sensors (accelerometer)

- Cellular Radios (GSM/CDMA/LTE)

- Flash Memory

- Removable Storage (i.e.- SD)

- USB ports

- Wireless Interfaces

- 802.11

- Bluetooth

- NFC

- RFID

- Touch Screen

- Hardware Keyboard

- Microphone

- Camera

- Authentication

- Method

- Knowledge based

- Token based

- Biometrics

- Input Type

- Keyboard

- Touch screen

- Hardware peripheral

- Decision Process

- Local (on device)

- Remote (off device)

- Method

- Define app architecture relative to OS stack + security model

- What should or shouldn't the app do?

Mobile Data

This section defines what purpose does the app serve from a business perspective and what data the app store, transmit and receive. It’s also important to review data flow diagrams to determine exactly how data is handled and managed by the application.

- What is the business function of the app?

- What data does the application store/process (provide data flow diagram)

- This diagram should outline network, device file system and application data flows

- How is data transmitted between third party API’s and app(s)

- Are there different data handling requirements between different mobile platforms? (iOS/Android/Blackberry/Windows/J2ME)

- Does the app use cloud storage APIs (Dropbox, Google Drive, iCloud, Lookout) for device data backups

- Does personal data intermingle with corporate data?

- Is there specific business logic built into the app to process data?

- What does the data give you (or an attacker) access to

- Data at Rest

- Example: Do stored credentials provide authentication?

- Data in Transit

- Example: Do stored keys allow you to break crypto functions (data integrity)?

- Third party data, is it being stored/transmitted?

- What is the privacy requirements of user data

- Example: UDID or Geolocation on iOS transmitted to 3rd party

- Are there regulatory requirements to meet specific to user privacy?

- How does other data on the device affect the app (sandboxing restrictions enforced?)