This site is the archived OWASP Foundation Wiki and is no longer accepting Account Requests.

To view the new OWASP Foundation website, please visit https://owasp.org

Difference between revisions of "Testing for Bypassing Authentication Schema (OTG-AUTHN-004)"

(→References) |

m (Change heading formatting) |

||

| (36 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Template:OWASP Testing Guide | + | {{Template:OWASP Testing Guide v4}} |

| − | == | + | == Summary == |

| − | While most | + | While most applications require authentication to gain access to private information or to execute tasks, not every authentication method is able to provide adequate security. Negligence, ignorance, or simple understatement of security threats often result in authentication schemes that can be bypassed by simply skipping the log in page and directly calling an internal page that is supposed to be accessed only after authentication has been performed. |

| − | |||

| − | In addition | + | In addition, it is often possible to bypass authentication measures by tampering with requests and tricking the application into thinking that the user is already authenticated. This can be accomplished either by modifying the given URL parameter, by manipulating the form, or by counterfeiting sessions. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Problems related to the authentication schema can be found at different stages of the software development life cycle (SDLC), like the design, development, and deployment phases: | |

| + | * In the design phase errors can include a wrong definition of application sections to be protected, the choice of not applying strong encryption protocols for securing the transmission of credentials, and many more. | ||

| + | * In the development phase errors can include the incorrect implementation of input validation functionality or not following the security best practices for the specific language. | ||

| + | * In the application deployment phase, there may be issues during the application setup (installation and configuration activities) due to a lack in required technical skills or due to the lack of good documentation. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == Black Box testing | + | == How to Test == |

| − | There are several methods | + | === Black Box testing === |

| − | * Direct page request | + | There are several methods of bypassing the authentication schema that is used by a web application: |

| − | * Parameter | + | * Direct page request ([[Forced_browsing|forced browsing]]) |

| − | * Session ID | + | * Parameter modification |

| − | * | + | * Session ID prediction |

| + | * SQL injection | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | ====Direct page request==== | |

| − | + | If a web application implements access control only on the log in page, the authentication schema could be bypassed. For example, if a user directly requests a different page via forced browsing, that page may not check the credentials of the user before granting access. Attempt to directly access a protected page through the address bar in your browser to test using this method. | |

| − | [[Image:basm-directreq.jpg]] | + | <center>[[Image:basm-directreq.jpg]]</center> |

| − | + | ====Parameter Modification==== | |

| − | Another problem related to authentication design is | + | Another problem related to authentication design is when the application verifies a successful log in on the basis of a fixed value parameters. A user could modify these parameters to gain access to the protected areas without providing valid credentials. In the example below, the "authenticated" parameter is changed to a value of "yes", which allows the user to gain access. In this example, the parameter is in the URL, but a proxy could also be used to modify the parameter, especially when the parameters are sent as form elements in a POST request or when the parameters are stored in a cookie. |

| − | |||

<pre>http://www.site.com/page.asp?authenticated=no </pre> | <pre>http://www.site.com/page.asp?authenticated=no </pre> | ||

| Line 52: | Line 46: | ||

Connection: close | Connection: close | ||

Content-Type: text/html; charset=iso-8859-1 | Content-Type: text/html; charset=iso-8859-1 | ||

| − | + | ||

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//IETF//DTD HTML 2.0//EN"> | <!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//IETF//DTD HTML 2.0//EN"> | ||

<HTML><HEAD> | <HTML><HEAD> | ||

</HEAD><BODY> | </HEAD><BODY> | ||

| − | <H1>You Are | + | <H1>You Are Authenticated</H1> |

| − | </BODY></HTML></pre> | + | </BODY></HTML> |

| + | </pre> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <center>[[Image:basm-parammod.jpg]]</center> | ||

| − | + | ====Session ID Prediction==== | |

| + | Many web applications manage authentication by using session identifiers (session IDs). Therefore, if session ID generation is predictable, a malicious user could be able to find a valid session ID and gain unauthorized access to the application, impersonating a previously authenticated user. | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | In the following figure, values inside cookies increase linearly, so it could be easy for an attacker to guess a valid session ID. | |

| − | |||

| + | <center>[[Image:basm-sessid.jpg]]</center> | ||

| − | |||

| + | In the following figure, values inside cookies change only partially, so it's possible to restrict a brute force attack to the defined fields shown below. | ||

| − | |||

| + | <center>[[Image:basm-sessid2.jpg]]</center> | ||

| − | |||

| + | ====SQL Injection (HTML Form Authentication)==== | ||

| + | SQL Injection is a widely known attack technique. This section is not going to describe this technique in detail as there are several sections in this guide that explain injection techniques beyond the scope of this section. | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | <center>[[Image:basm-sqlinj.jpg]]</center> | |

| − | + | The following figure shows that with a simple SQL injection attack, it is sometimes possible to bypass the authentication form. | |

| − | + | <center>[[Image:basm-sqlinj2.gif]]</center> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | === Gray Box Testing === | |

| − | + | If an attacker has been able to retrieve the application source code by exploiting a previously discovered vulnerability (e.g., directory traversal), or from a web repository (Open Source Applications), it could be possible to perform refined attacks against the implementation of the authentication process. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | In the following example (PHPBB 2.0.13 - Authentication Bypass Vulnerability), at line 5 unserialize() function | + | In the following example (PHPBB 2.0.13 - Authentication Bypass Vulnerability), at line 5 the unserialize() function parses a user supplied cookie and sets values inside the $row array. At line 10 the user's MD5 password hash stored inside the back end database is compared to the one supplied. |

| − | <pre>1. if ( isset($HTTP_COOKIE_VARS[$cookiename . '_sid']) || | + | <pre> |

| + | 1. if ( isset($HTTP_COOKIE_VARS[$cookiename . '_sid']) || | ||

2. { | 2. { | ||

3. $sessiondata = isset( $HTTP_COOKIE_VARS[$cookiename . '_data'] ) ? | 3. $sessiondata = isset( $HTTP_COOKIE_VARS[$cookiename . '_data'] ) ? | ||

| Line 114: | Line 109: | ||

12. { | 12. { | ||

13. $autologin = ( isset($HTTP_POST_VARS['autologin']) ) ? TRUE : 0; | 13. $autologin = ( isset($HTTP_POST_VARS['autologin']) ) ? TRUE : 0; | ||

| − | 14. }</pre> | + | 14. } |

| + | </pre> | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | In PHP, a comparison between a string value and a boolean value (1 - "TRUE") is always "TRUE", so by supplying the following string (the important part is "b:1") to the unserialize() function, it is possible to bypass the authentication control: | |

| − | + | ||

| + | a:2:{s:11:"autologinid";b:1;s:6:"userid";s:1:"2";} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Tools== | ||

| + | * [[OWASP WebScarab Project|WebScarab]] | ||

| + | * [[OWASP WebGoat Project|WebGoat]] | ||

| + | * [https://www.owasp.org/index.php/OWASP_Zed_Attack_Proxy_Project OWASP Zed Attack Proxy (ZAP)] | ||

| + | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

'''Whitepapers'''<br> | '''Whitepapers'''<br> | ||

| − | David Endler | + | * Mark Roxberry: "PHPBB 2.0.13 vulnerability" |

| − | http://www.cgisecurity.com/lib/SessionIDs.pdf | + | * David Endler: "Session ID Brute Force Exploitation and Prediction" - http://www.cgisecurity.com/lib/SessionIDs.pdf |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 14:44, 5 August 2014

This article is part of the new OWASP Testing Guide v4.

Back to the OWASP Testing Guide v4 ToC: https://www.owasp.org/index.php/OWASP_Testing_Guide_v4_Table_of_Contents Back to the OWASP Testing Guide Project: https://www.owasp.org/index.php/OWASP_Testing_Project

Summary

While most applications require authentication to gain access to private information or to execute tasks, not every authentication method is able to provide adequate security. Negligence, ignorance, or simple understatement of security threats often result in authentication schemes that can be bypassed by simply skipping the log in page and directly calling an internal page that is supposed to be accessed only after authentication has been performed.

In addition, it is often possible to bypass authentication measures by tampering with requests and tricking the application into thinking that the user is already authenticated. This can be accomplished either by modifying the given URL parameter, by manipulating the form, or by counterfeiting sessions.

Problems related to the authentication schema can be found at different stages of the software development life cycle (SDLC), like the design, development, and deployment phases:

- In the design phase errors can include a wrong definition of application sections to be protected, the choice of not applying strong encryption protocols for securing the transmission of credentials, and many more.

- In the development phase errors can include the incorrect implementation of input validation functionality or not following the security best practices for the specific language.

- In the application deployment phase, there may be issues during the application setup (installation and configuration activities) due to a lack in required technical skills or due to the lack of good documentation.

How to Test

Black Box testing

There are several methods of bypassing the authentication schema that is used by a web application:

- Direct page request (forced browsing)

- Parameter modification

- Session ID prediction

- SQL injection

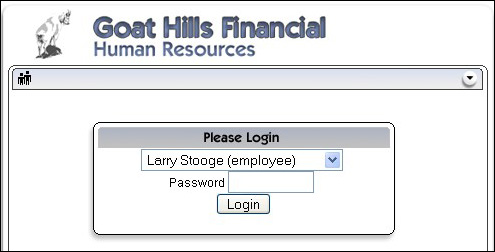

Direct page request

If a web application implements access control only on the log in page, the authentication schema could be bypassed. For example, if a user directly requests a different page via forced browsing, that page may not check the credentials of the user before granting access. Attempt to directly access a protected page through the address bar in your browser to test using this method.

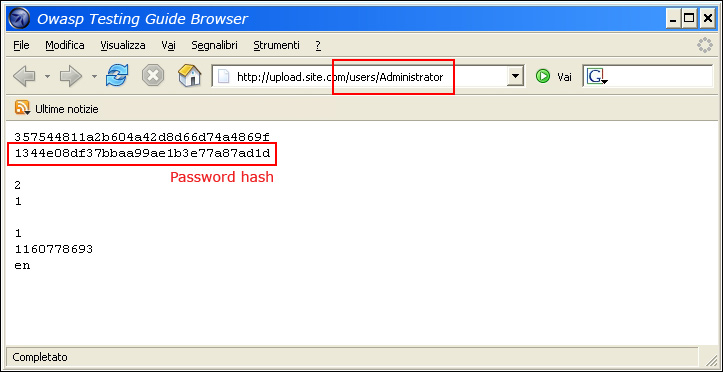

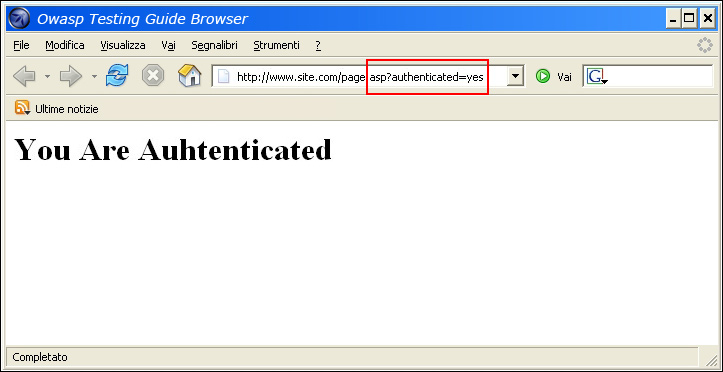

Parameter Modification

Another problem related to authentication design is when the application verifies a successful log in on the basis of a fixed value parameters. A user could modify these parameters to gain access to the protected areas without providing valid credentials. In the example below, the "authenticated" parameter is changed to a value of "yes", which allows the user to gain access. In this example, the parameter is in the URL, but a proxy could also be used to modify the parameter, especially when the parameters are sent as form elements in a POST request or when the parameters are stored in a cookie.

http://www.site.com/page.asp?authenticated=no

raven@blackbox /home $nc www.site.com 80

GET /page.asp?authenticated=yes HTTP/1.0

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Sat, 11 Nov 2006 10:22:44 GMT

Server: Apache

Connection: close

Content-Type: text/html; charset=iso-8859-1

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//IETF//DTD HTML 2.0//EN">

<HTML><HEAD>

</HEAD><BODY>

<H1>You Are Authenticated</H1>

</BODY></HTML>

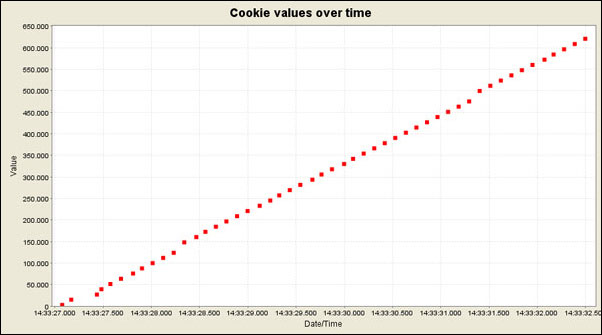

Session ID Prediction

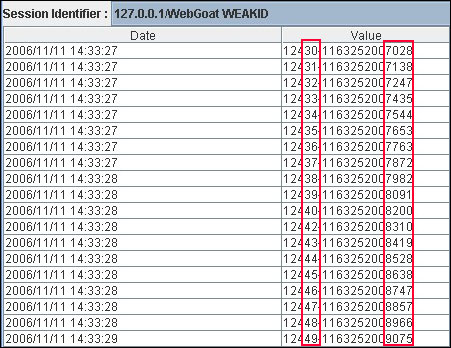

Many web applications manage authentication by using session identifiers (session IDs). Therefore, if session ID generation is predictable, a malicious user could be able to find a valid session ID and gain unauthorized access to the application, impersonating a previously authenticated user.

In the following figure, values inside cookies increase linearly, so it could be easy for an attacker to guess a valid session ID.

In the following figure, values inside cookies change only partially, so it's possible to restrict a brute force attack to the defined fields shown below.

SQL Injection (HTML Form Authentication)

SQL Injection is a widely known attack technique. This section is not going to describe this technique in detail as there are several sections in this guide that explain injection techniques beyond the scope of this section.

The following figure shows that with a simple SQL injection attack, it is sometimes possible to bypass the authentication form.

Gray Box Testing

If an attacker has been able to retrieve the application source code by exploiting a previously discovered vulnerability (e.g., directory traversal), or from a web repository (Open Source Applications), it could be possible to perform refined attacks against the implementation of the authentication process.

In the following example (PHPBB 2.0.13 - Authentication Bypass Vulnerability), at line 5 the unserialize() function parses a user supplied cookie and sets values inside the $row array. At line 10 the user's MD5 password hash stored inside the back end database is compared to the one supplied.

1. if ( isset($HTTP_COOKIE_VARS[$cookiename . '_sid']) ||

2. {

3. $sessiondata = isset( $HTTP_COOKIE_VARS[$cookiename . '_data'] ) ?

4.

5. unserialize(stripslashes($HTTP_COOKIE_VARS[$cookiename . '_data'])) : array();

6.

7. $sessionmethod = SESSION_METHOD_COOKIE;

8. }

9.

10. if( md5($password) == $row['user_password'] && $row['user_active'] )

11.

12. {

13. $autologin = ( isset($HTTP_POST_VARS['autologin']) ) ? TRUE : 0;

14. }

In PHP, a comparison between a string value and a boolean value (1 - "TRUE") is always "TRUE", so by supplying the following string (the important part is "b:1") to the unserialize() function, it is possible to bypass the authentication control:

a:2:{s:11:"autologinid";b:1;s:6:"userid";s:1:"2";}

Tools

References

Whitepapers

- Mark Roxberry: "PHPBB 2.0.13 vulnerability"

- David Endler: "Session ID Brute Force Exploitation and Prediction" - http://www.cgisecurity.com/lib/SessionIDs.pdf